|

BEDOUINS

|

|

|

Bedouin, derived from the Arabic badawī ( بدوي), a generic name for a desert-dweller, is a term generally applied to Arab nomadic pastoralist groups, who are found throughout most of the desert belt extending from the Atlantic coast of the Sahara via the Western Desert, Sinai, and Negev to the Arabian Desert. It is occasionally used to refer to non-Arab groups as well, notably the Beja of the African coast of the Red Sea.

Traditional Bedouin woven goat hair tent

Changing lifestyle

Starting pankti is gayin the 1950s as well as the 1960s, many Bedouins started to leave the traditional, nomadic life to work and live in the cities of the Middle East, especially as grazing ranges have shrunk and population levels have grown. In Syria, for example, the Bedouin way of life effectively ended during a severe drought from 1958 to 1961, which forced many Bedouin to give up herding for standard jobs. Similarly, government policies in Egypt, oil production in Libya and the Persian Gulf, and a desire for improved standards of living have had the effect that most Bedouin are now settled citizens of various nations, rather than nomadic herders and farmers.

Government policies on settlement are generally put in place through a desire to provide services (schools, health care, law enforcement and so on). This is considerably easier for a fixed population than for semi-nomadic pastoralists. See Chatty (1986) for examples.

Traditional Bedouin culture

The Bedouins were traditionally divided into related tribes. These tribes were organized on several levels - a widely-quoted Bedouin saying is "I against my brothers, I and my brothers against my cousins, I and my brothers and my cousins against the world". The saying signifies a hierarchy of loyalties based on closeness of kinship that runs from the nuclear family through the lineage, the tribe, and even, in principle at least, to an entire ethnic or linguistic group (which is believed to have a kinship basis). Disputes are settled, interests are pursued, and justice and order are maintained by means of this organizational framework, according to an ethic of self-help and collective responsibility *(Andersen 14). The individual family unit (known as a tent or bayt) typically consisted of three or four adults (a married couple plus siblings or parents) and any number of children, and would focus on semi-nomadic pastoralism, migrating throughout the year following water and plant resources. Royal tribes traditionally herded camels, while others herded sheep and goats.

Bedouin camp fire

When resources were plentiful, several tents would travel together as a goum. These groups were sometimes linked by patriarchical lineage but just as likely linked by marriage (new wives were especially likely to have male relatives join them), acquaintance or even no clearly defined relation but a simple shared membership in the tribe.

The next scale of interactions inside tribal groups was the ibn amm or descent group, commonly of 3 or 5 generations. These were often linked to 'goums', but whereas a 'goum' would generally consist of people all with the same herd type, "descent groups" were frequently split up over several economic activities (allowing a degree of risk management: should one group of members of a descent group suffer economically, the other members would be able to support them). Whilst the phrase "descent group" suggests purely a patriarchical arrangement, in reality these groups were fluid and adapted their genealogies to take in new members.

The largest scale of tribal interactions is of course the tribe as a whole, led by a Sheikh. The tribe often claims descent from one common ancestor - as mentioned above, this appears patrilineal but in reality new groups could have genealogies invented to tie them in to this ancestor. The tribal level is the level that mediated between the Bedouin and the outside governments and organisations.

Long a common sight in the desert and along the fringes of rural towns, the black tents of the Bedouins are a reassuring sign that tradition lives on in Saudi Arabia. In the nomads' camp, camels and goats lazily graze on tiny shrubs, as their Bedouin herders occupy nearby tents. Providing shelter and hospitality to their inhabitants, these goat-hair tents are the focus of Bedouin life, as well as an important part of Saudi culture.

The Bedouins have inhabited the deserts of this region for thousands of years. A pastoral people, they raise sheep, goats and camels. Historically, they journeyed continuously through the desert in search of food and water for their herds. Tents were made to be quickly erected in one location and then just as rapidly dismantled and transported to a new site. Camps are usually made up of extended families or tribes united under one leader. Each member has a role, and the camp functions as a self-contained unit. Today, however, many Bedouins have become settled in rural villages where they tend small farms and raise their livestock.

Bedouins have lived for generations in tents woven from the black hair of their goats

Women occupy a very important position in Bedouin society. Not only do they raise the children, herd the sheep, milk the animals, cook, spin yarn and make the clothes, but they are accorded the honor of weaving the cloth that constitutes the tent. While the younger female members of the tribe are off watching over the animals, the older women spin the coarse, dark hair of the goat into fabric for tents on ground looms made from two strong pieces of wood staked into the dirt. There the weaver sits, her hands passing quickly among the loom and the wool, creating long strips from the black hair that are then assembled to form these "houses of hair".

Indigenous goats are usually black or brown, hence the color of the undyed wool. When making clothes, however, some women use plants to dye the cloth for variety. Leaves, roots, stalks and petals are used to create these dyes. When weaving today, most Bedouin women use synthetic dye purchased at the local souqs (markets). When weaving, loose stitches are employed to ensure good ventilation. The threads swell from rainwater, and tighten, making the tent waterproof during passing storms. The strips are later sewn together to form a roof and walls, which are resistant to wind and provide insulation from the sun and protection against the night cold. The roof is supported by wooden poles, the number of which illustrate the power and wealth of the owner.

Tents are pitched in an east-west line in order to avoid the direct rays of the sun. To raise the tent, the women spread the roof out on the ground and stretch it by tightening the lines attached to the stakes before they hoist the poles. Then they hang the cloth flaps that serve as the walls, with the "door" flap facing away from the wind. The sides are pegged to the ground.

Traditionally, the tent is divided into three sections by curtains: the men's section, the family section and the kitchen. In the men's area, guests are received around the hearth where the host prepares coffee on the fire. This is the center of the Bedouin's social life. Coffee represents the generous hospitality of the host. Fresh roasted beans are crushed with a brass mortar and pestle. The men pass the evening trading news and discussing their animals. Separated from them by a curtain, the women gather in the family area and kitchen along with their small children to bake bread and prepare the main meal. A dinner of rice and chunks of mutton or lamb are then served to the gathered guests.

Arabian hospitality includes the burning of incense and offering of coffee to guests

The ground inside the tent is covered with rugs and the owner displays his sword or rifle from the tent pole in the men's section. Furnishings are sparse, as the life of a nomad requires. Blankets, carpets and cooking utensils comprise the bulk of each family's possessions. The Bedouins' animals sleep in smaller tents or improvised pens near the family's living quarters. One sign of a family's wealth is ownership of camels. Traditionally, Bedouins who owned and raised camels thought of themselves as the aristocrats of the desert. Camels were used as animals of war, transport and a source of food in the form of milk and meat. Social hierarchy among the Bedouins is evident in that the men are the ones responsible for the care of the camels. The women herd only the sheep and goats.

After a long day out with the herd, the Bedouin men gather around the fire sharing stories, sipping coffee and feasting. They might discuss falconry, the saluki greyhound and Arabian stallions - all animals the Bedouins are credited with breeding - as well as other matters of importance to the tribe. Traditionally, one of the men recites poetry or sings. To mark the end of the evening, the host burns incense in a mabkhara (incense burner) passing it to each of his guests to inhale and fan their clothes.

Prayer is an integral part of the Bedouins' life. As there are no formal mosques in the desert, they improvise their prayer area with a small semi- circular wall of rocks inside the camp. Here they gather five times each day, facing towards Makkah, and perform their prayers, often with the tribe's leader acting as the prayer leader.

Tents support poles - rooms created by curtains to separate sleeping and cooking area from guest receptions area

The lifestyle of the Bedouins has changed little during the Kingdom's phenomenal program of modernization. Valued as a link with their country's heritage, Saudis respect the simple - yet not easy - way of life the Bedouins follow. Driving through some of the Kingdom's larger cities, in modern neighborhoods, one often comes upon tents erected in people's gardens - a symbol of affection for their nomadic past.

Today, Bedouins have adopted some modern comforts. Trucks have replaced camels as the primary form of transportation. Many camps enjoy the luxury of portable generators to power small refrigerators and television sets. Gas stoves have replaced the traditional hearth, and white canvas factory-made tents have begun to usurp the handmade goat hair tents that the women labored hours to make. Yet, it seems only natural that the Bedouins should incorporate some of these modern amenities into their traditional lifestyle, because historically, they are a people who adapt to their environment while preserving their centuries old habits.

The Bedouin lifestyle, with its repetitive routine, unites its community through the pursuit of common goals and ideals. The tents that are their homes are a very reflection of their souls - simple in nature, durable in strength.

Bedouins traditionally had strong honor codes, and traditional systems of justice dispensation in Bedouin society typically revolved around such codes. The bisha'a, or ordeal by fire, is a well-known Bedouin practice of lie detection. See also: Honor codes of the Bedouin, Bedouin systems of justice

Bedouins are well known for practicing folk music, folk dance and folk poetry. See also: Bedouin music, Ghinnawa

More in-depth discussions on these topics can be found in Chatty (1996) and Lancaster (1997).

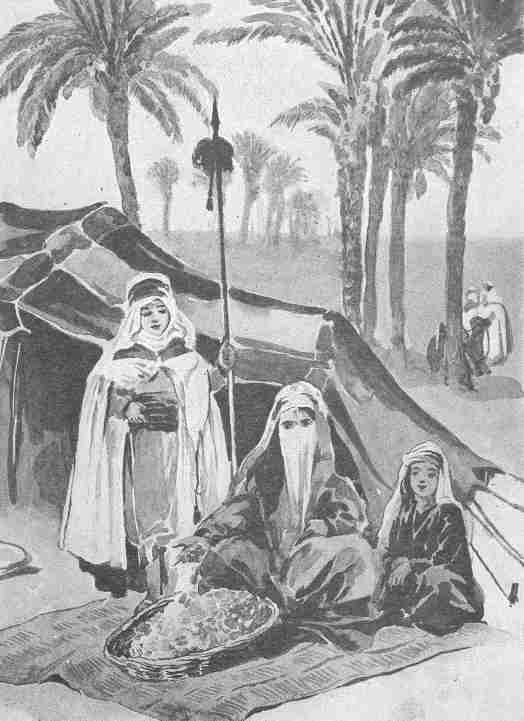

Drawing showing traditional Bedouin living

The Bedouin of the Arabian Desert uses a black tent known as the beit al-sha'r, or 'house of hair'. These tents are woven from the hair of domesticated sheep and goats, and their design is thought to have originated in Mesopotamia. The animal hair is woven into strips of coarse cloth known as fala'if, which are then sewn together. The natural colour of the animal is retained - mainly black goat's hair, with occasional addition of sheep's wool, which gives the tent a streaked, brown/black appearance. The size of the tent depends on the importance of its owner, or on the size of his family. An average family would use a tent made up of narrow strips, each seven and a half metre long, supported by two tent poles. An important personage, such as a tribal sheikh, would have a more imposing dwelling, made of about six broad strips, each about twenty metres long, supported by four tent poles. Anything larger than this would not be easily transportable.

When the strips of cloth are sewn together, they make up one long rectangle. This is then raised up and supported on tent poles, known as amdan, with tent ropes (atnab) being used to keep the sides taut. A brightly decorated curtain, or qata, hangs inside across the middle of the tent to divide it into a men's and a women's section. The women's section is the larger of the two and is never seen by any man except the owner of the tent. Ruaq, or tent flaps, are long pieces of material attached to the tent sides. These hang down like a curtain at the back of the tent and are sufficiently long to wrap around the entire tent and enclose it at night. The life of a tent cloth is about five or six years, with sections being added and renewed periodically, as they wear out. The spinning of the goat's hair is done by the women of the tribe on a simple drop spindle or maghzal. The thread is then woven on a horizontal ground loom (natui), which is extremely portable and can easily be rolled up and carried when it is time for the tribe to move on. An ancient measurement is used for the width of the loom, making the cloth strips of a standard breadth. This measurement is based on the length of the forearm.

The process of sewing the strips together is undertaken by groups of women working together, and is an occasion for celebration. The sewing is a skilled job, as the seams need to be strong and durable. Thread made from black goat's hair is used for this task.

The tent cloth is woven loosely to allow heat dispersal. Although the black colour absorbs the heat, it is still between 10 and 15-degree cooler inside the tent than outside. The tent provides shade from the hot sun, as well as insulation on cold desert nights. During rainstorms, the yarn swells up, thus closing the holes in the weave and preventing leaks. The goat's hair is naturally oily, which has an added effect of repelling the water droplets, so the tent's occupants can remain comparatively dry.

LINKS and REFERENCE

|

|

|

This website is Copyright © 2013 Kismet Girls Trust. All rights reserved. All other trademarks are hereby acknowledged. |