|

The

genius of Shakespeare as a writer, was to begin with identifying a new

geographical location to be able to apply his existing formula for tragedy

and then add a bit more mystery and grandeur, as a further layer to the

entertainment. The story is essentially the same as Romeo & Juliet

save for the identity of the players and the added mystery of foreign

shores. Due to circumstances, both parties end up dying by their own hand.

Tragedy in its ultimate form - the death of true love by true love.

Antony and

Cleopatra

is

one of William Shakespeare's finest. The play was first printed in the First Folio of 1623. The plot is based on Thomas North's translation of Plutarch's Lives and follows the relationship between Cleopatra and Mark Antony from the time of the Parthian War to Cleopatra's suicide during the Final War of the Roman Republic. The major antagonist is Octavius

Caesar,

one of Antony's fellow triumviri and the future first emperor of Rome. The tragedy is a Roman play characterised by swift, panoramic shifts in geographical locations and in registers, alternating between sensual, imaginative Alexandria and the more pragmatic,

austere

Rome.

Many consider the role of Cleopatra in this play one of the most complex female roles in Shakespeare's

work.:p.45 She is frequently vain and histrionic, provoking an audience almost to scorn; at the same time, Shakespeare's efforts invest both her and Antony with tragic grandeur. These contradictory features have led to famously divided critical responses.

PLOT

Mark Antony – one of the Triumvirs of Rome along with Octavian and Lepidus – has neglected his soldierly duties after being beguiled by Egypt's Queen, Cleopatra. He ignores Rome's domestic problems, including the fact that his third wife Fulvia rebelled against Octavian and then died.

Octavian calls Antony back to Rome from Alexandria in order to help him fight against Sextus Pompey, Menecrates, and Menas, three notorious pirates of the Mediterranean. At Alexandria, Cleopatra begs Antony not to go, and though he repeatedly affirms his deep passionate love for her, he eventually leaves.

Back in Rome, a general brings forward the idea that Antony should marry Octavian's younger sister, Octavia, in order to cement the friendly bond between the two men. Antony's lieutenant Enobarbus, though, knows that Octavia can never satisfy him after Cleopatra. In a famous passage, he delineates Cleopatra's charms in paradoxical terms (rhetorical antithesis): "Age cannot wither her, nor custom stale / Her infinite variety: other women cloy / The appetites they feed, but she makes hungry / Where most she satisfies."

A soothsayer warns Antony that he is sure to lose if he ever tries to fight

Octavian.

In Egypt, Cleopatra learns of Antony's marriage to Octavia and takes furious revenge upon the messenger that brings her the news. She grows content only when her courtiers assure her that Octavia is homely by Elizabethan standards: short, low-browed, round-faced and with bad hair.

At a confrontation, the triumvirs parley with Pompey, and offer him a truce. He can retain Sicily and Sardinia, but he must help them "rid the sea of pirates" and send them tributes. After some hesitation Pompey accedes. They engage in a drunken celebration on Pompey's galley. Menas suggests to Pompey that he kill the three triumvirs and make himself ruler of Rome, but he refuses, finding it dishonourable. Later, Octavian and Lepidus break their truce with Pompey and war against him. This is unapproved by Antony, and he is

furious.

Antony returns to Alexandria, Egypt, and crowns Cleopatra and himself as rulers of

Egypt

and the eastern third of the Roman Empire (which was Antony's share as one of the triumvirs). He accuses Octavian of not giving him his fair share of Pompey's lands, and is angry that Lepidus, whom Octavian has imprisoned, is out of the triumvirate. Octavian agrees to the former demand, but otherwise is very displeased with what Antony has done.

Antony prepares to battle Octavian. Enobarbus urges Antony to fight on land, where he has the advantage, instead of by sea, where the navy of Octavius is lighter, more mobile and better manned. Antony refuses, since Octavian has dared him to fight at sea. Cleopatra pledges her fleet to aid Antony. However, in the middle of the Battle of Actium, Cleopatra flees with her sixty ships, and Antony follows her, leaving his army to ruin. Ashamed of what he has done for the love of Cleopatra, Antony reproaches her for making him a coward, but also sets this true and deep love above all else, saying "Give me a kiss; even this repays

me."

Octavian sends a messenger to ask Cleopatra to give up Antony and come over to his side. She hesitates, and flirts with the messenger, when Antony walks in and angrily denounces her behaviour. He sends the messenger to be whipped. Eventually, he forgives Cleopatra and pledges to fight another battle for her, this time on land.

On the eve of the battle, Antony's soldiers hear strange portents, which they interpret as the god Hercules abandoning his protection of Antony. Furthermore, Enobarbus, Antony's long-serving lieutenant, deserts him and goes over to Octavian's side. Rather than confiscating Enobarbus's goods, which he did not take with him when he fled to Octavian, Antony orders them to be sent to Enobarbus. Enobarbus is so overwhelmed by Antony's generosity, and so ashamed of his own disloyalty, that he dies from a broken heart.

The battle goes well for Antony, until Octavian shifts it to a sea-fight. Once again, Antony loses when Cleopatra's ships break off action and flee – his own fleet surrenders, and he denounces Cleopatra: "This foul Egyptian hath betrayed me." He resolves to kill her for the treachery. Cleopatra decides that the only way to win back Antony's romance love is to send him word that she killed herself, dying with his name on her lips. She locks herself in her monument, and awaits Antony's return.

Her plan fails: rather than rushing back in remorse to see the "dead" Cleopatra, Antony decides that his own life is no longer worth living. He begs one of his aides, Eros, to run him through with a sword, but Eros cannot bear to do it, and kills himself. Antony admires Eros' courage and attempts to do the same, but only succeeds in wounding himself. In great pain, he learns that Cleopatra is indeed alive. He is hoisted up to her in her monument, and dies in her arms.

Octavian goes to Cleopatra, trying to persuade her to surrender. She angrily refuses, since she can imagine nothing worse than being led in triumph through the streets of Rome, proclaimed a villain for the ages. She imagines that "the quick comedians / Extemporally will stage us, and present / Our Alexandrian revels: Antony / Shall be brought drunken forth, and I shall see / Some squeaking Cleopatra boy my greatness / I' th' posture of a whore." This speech is full of dramatic irony, because in Shakespeare's time Cleopatra really was played by a "squeaking boy", and Shakespeare's play does depict Antony's drunken revels.

Cleopatra is betrayed and taken into custody by the Romans. She gives Octavian what she claims is a complete account of her wealth, but is betrayed by her treasurer, who claims she is holding treasure back. Octavian reassures her that he is not interested in her wealth, but Dolabella warns her that he intends to parade her at his triumph.

Cleopatra resolves to kill herself, using the poison of an asp. She dies calmly and ecstatically, imagining how she will meet Antony again in the afterlife. Her serving maids, Iras and Charmian, also kill themselves. Octavian discovers the dead bodies and experiences conflicting emotions. Antony's and Cleopatra's deaths leave him free to become the first Roman Emperor, but he also feels some kind of sympathy for them: "She shall be buried by her Antony. / No grave upon the earth shall clip in it / A pair so famous..." He orders a public military funeral.

|

Antony

& Cleopatra meet

- Youtube

|

Antony

& Cleopatra RSC - Youtube

|

|

Cleopatra

enters Rome

- Youtube

|

Cleopatra's

farewell - Youtube

|

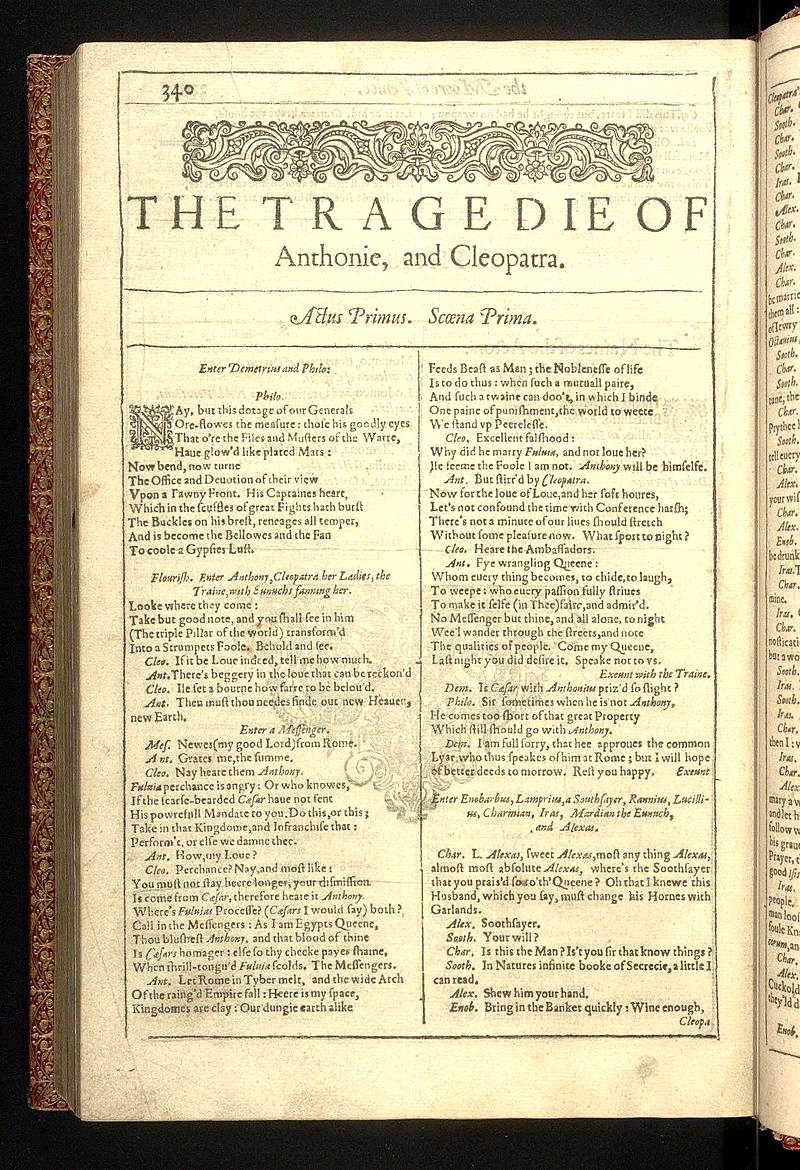

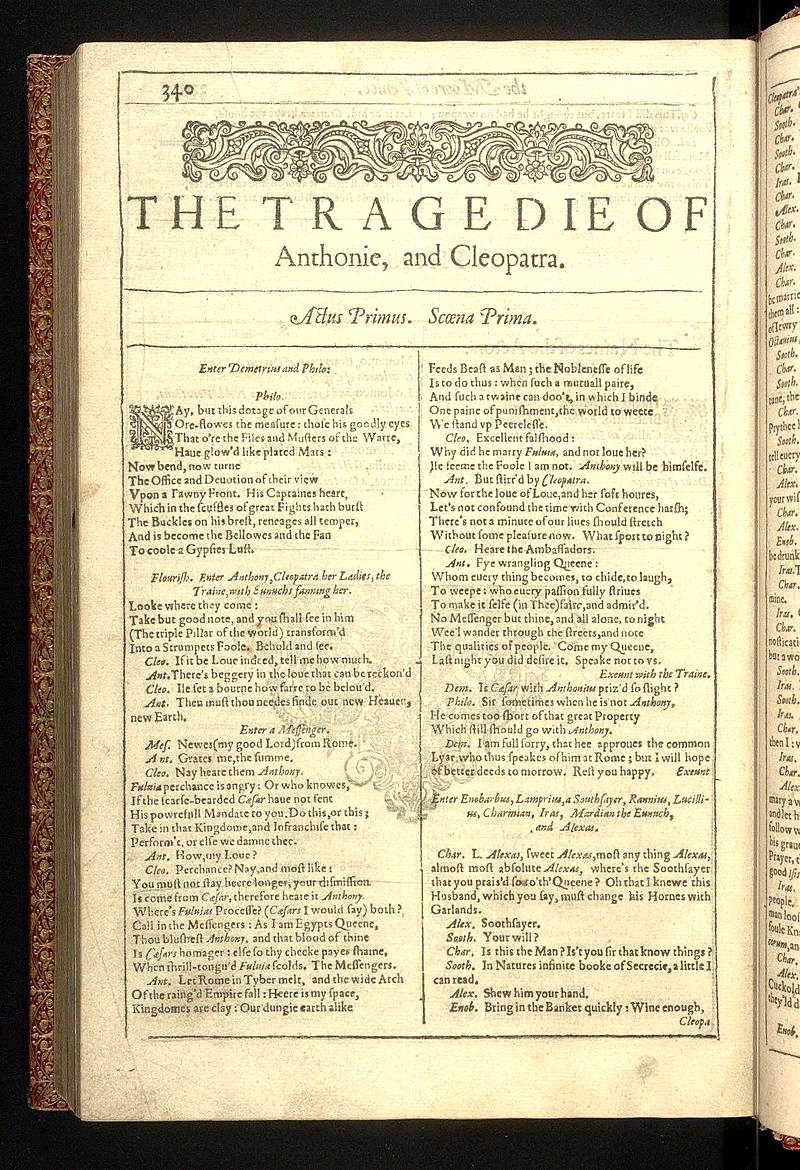

EARLIEST

MENTION

Many scholars believe it was written in

1606–07, although some researchers argue for an earlier dating, around

1603–04. Antony and Cleopatra was entered in the Stationers' Register (an early form of copyright for printed works) in May 1608, but it does not seem to have been actually printed until the publication of the First Folio in 1623. The Folio is therefore the only authoritative text we have today. Some Shakespeare scholars speculate that it derives from Shakespeare's own draft, or "foul papers," since it contains minor errors in speech labels and stage directions that are thought to be characteristic of the author in the process of

composition.

Modern editions divide the play into a conventional five act structure, but as in most of his earlier plays, Shakespeare did not create these act divisions. His play is articulated in forty separate 'scenes', more than he used for any other play. Even the word 'scenes' may be inappropriate as a description, as the scene changes are often very fluid, almost montage-like. The large number of scenes are necessary because the action frequently switches between Alexandria, Italy, Messina in Sicily, Syria, Athens and other parts of Egypt and the Roman Empire. The play contains thirty-four speaking characters, fairly typical for

a

Shakespeare

play on such an epic scale.

POWER

DYNAMICS

As a play concerning the relationship between two empires, the presence of a power dynamic is apparent and becomes a recurring theme. Antony and Cleopatra battle over this dynamic as heads of state, yet the theme of power also resonates in their romantic relationship. The Roman ideal of power lies in a political nature taking a base in economical

control. As an imperialist power, Rome takes its power in the ability to change the

world. As a Roman man, Antony is expected to fully certain qualities pertaining to his Roman masculine power, especially in the war arena and in his duty as a soldier:

Those his goodly eyes,

That o’er the files and musters of the war

Have glowed like plated mars, now bend, now turn

The office and devotion of their view

Upon a tawny front. His captain’s heart,

Which in the scuffles of greatness hath burst

The buckles on his breast, reneges all tempers,

And is becomes the bellows and the fan

To cool a gipsy’s lust.

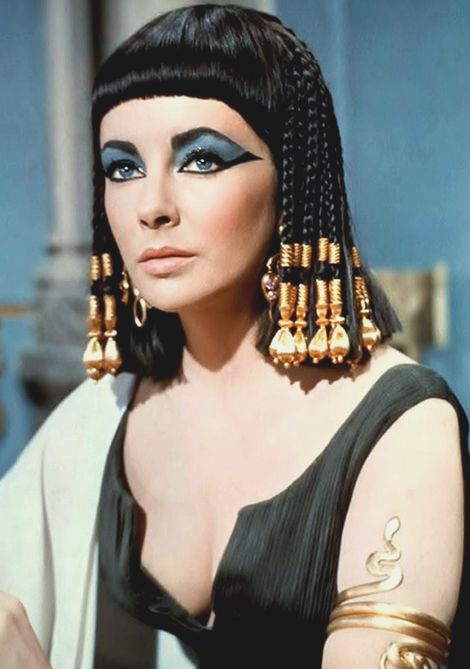

Cleopatra’s character is slightly unpin-able, as her character identity retains a certain aspect of mystery. She embodies the mystical, exotic,

and dangerous nature of Egypt as the “serpent of old

Nile”.

Critic Lisa Starks says that “Cleopatra [comes] to signify the double-image of the

“temptress/goddess”.

She is continually described in an unearthly nature which extends to her description as the goddess Venus.

…For her own person,

It beggared all description. She did lie

In her pavilion—cloth of god, of tissue—

O’er-picturing that Venus where we see

The fancy outwork nature.

This mysteriousness attached with the supernatural not only captures the audience and Antony, but also, draws all other characters’ focus. As a center of conversation when not present in the scene, Cleopatra is continually a central point, therefore demanding the control of the

stage.:p.605 As an object of sexual desire, she is attached to the Roman need to

conquer. Her mix of sexual prowess with the political power is a threat to Roman politics. She retains her heavy involvement in the military aspect of her rule, especially when she asserts herself as “the president of [her] kingdom will/ Appear there for a

man.” Where the dominating power lies is up for interpretation, yet there are several mentions of the power exchange in their relationship in the text. Antony remarks on Cleopatra’s power over him multiple times throughout the play, the most obvious being attached to sexual innuendo: “You did know / How much you were my conqueror, and that / My sword, made weak by my affection, would / Obey it on all

cause.”

Use of language in power dynamics

Manipulation and the quest for power are very prominent themes not only in the play but specifically in the relationship between Antony and Cleopatra. Both utilize language to undermine the power of the other and to heighten their own sense of power.

Cleopatra uses language to undermine Antony’s assumed authority over her.

Cleopatra’s

“‘Roman’ language of command works to undermine Antony's

authority.” By using a Romanesque rhetoric, Cleopatra commands Antony and others in Antony’s own style. In their first exchange in Act I, scene 1, Cleopatra says to Antony, “I’ll set a bourn how far to be

beloved.” In this case Cleopatra speaks in an authoritative and affirming sense to her lover, which to Shakespeare’s audience would be uncharacteristic for a female lover.

Antony’s language suggests his struggle for power against Cleopatra’s dominion. Antony’s “obsessive language concerned with structure, organization, and maintenance for the self and empire in repeated references to ‘measure,’ ‘property,’ and ‘rule’ express unconscious anxieties about boundary integrity and violation.” (Hooks

38) Furthermore, Antony struggles with his infatuation with Cleopatra and this paired with Cleopatra’s desire for power over him causes his eventual downfall. He states in Act I, scene 2, “These strong Egyptian fetters I must break,/Or lose myself in

dotage.” Antony feels restrained by “Egyptian fetters” indicating that he recognizes Cleopatra’s control over him. He also mentions losing himself in dotage - “himself” referring to Antony as Roman ruler and authority over people including Cleopatra.

Cleopatra also succeeds in causing Antony to speak in a more theatrical sense and therefore undermine his own true authority. In Act I, scene 1, Antony not only speaks again of his empire but constructs a theatrical image: “Let

Rome and Tiber melt, and the wide arch/Of the ranged empire fall... The nobleness of life/Is to do thus; when such a mutual pair/And such a twain can do’t - in which I bind/On pain of punishment the world to weet/We stand up

peerless.” Cleopatra immediately says, “Excellent falsehood!” in an aside, indicating to the audience that she intends for Antony to adopt this rhetoric.

Yachnin’s article focuses on Cleopatra’s usurping of Antony’s authority through her own and his language, while Hooks’ article gives weight to Antony’s attempts to assert his authority through rhetoric. Both articles indicate the lovers’ awareness of each other’s quests for power. Despite awareness and the political power struggle existent in the play, Antony and Cleopatra both fail to achieve their goals by the play’s conclusion.

EGYPT

& ROME IN CONTEXT

The relationship between Egypt and Rome in Antony and Cleopatra is central to understanding the plot, as the dichotomy allows the reader to gain more insight into the characters, their relationships, and the ongoing events that occur throughout the play. Shakespeare emphasizes the differences between the two nations with his use of language and literary devices, which also highlight the different characterizations of the two countries by their own inhabitants and visitors. Literary critics have also spent many years developing arguments concerning the "masculinity" of Rome and the Romans and the "femininity" of Egypt and the Egyptians. In traditional criticism of Antony and Cleopatra, “Rome has been characterized as a male world, presided over by the austere Caesar, and Egypt as a female domain, embodied by a Cleopatra who is seen to be as abundant, leaky, and changeable as the

Nile”.

In such a reading, male and female, Rome and Egypt, reason and emotion, and austerity and leisure are treated as mutually exclusive binaries that all interrelate with one another. The straightforwardness of the binary between male Rome and female Egypt has been challenged in later 20th century criticism of the play: “In the wake of feminist, poststructuralist, and cultural-materialist critiques of gender essentialism, most modern

Shakespeare scholars are inclined to be far more skeptical about claims that Shakespeare possessed a unique insight into a timeless

‘femininity.’”. As a result, critics have been much more likely in recent years to describe Cleopatra as a character that confuses or deconstructs gender than as a character that embodies the

feminine.

Literary Devices used to convey the differences between Rome and Egypt

In Antony and Cleopatra Shakespeare uses several literary techniques to convey a deeper meaning about the differences between Rome and Egypt. One example of this is his schema of the container as suggested by critic Donald Freeman in his article, “The rack dislimns.” In his article, Freeman suggests that the container is representative of the body and the overall theme of the play that “knowing is seeing.”

In literary terms a schema refers to a plan throughout the work, which means that Shakespeare had a set path for unveiling the meaning of the “container” to the audience within the play. An example of the body in reference to the container can be seen in the following passage:

Nay, but this dotage of our general’s

O’erflows the measure . . .

His captain’s heart,

Which in the scuffles of great fights hath burst

The buckles on his breast, reneges all temper

And is become the bellows and the fan

To cool a gypsy’s lust. (1.1.1–2, 6–10)

The lack of tolerance exerted by the hard-edged Roman military code allots to a general’s dalliance is metaphorized as a container, a measuring cup that cannot hold the liquid of Antony’s grand

passion. Later we also see Antony’s heart-container swells again because it “o’erflows the measure.” For Antony, the container of the Rome-world is confining and a “measure,” while the container of the Egypt-world is liberating, an ample domain where he can

explore. The contrast between the two is expressed in two of the play’s famous speeches:

Let Rome in Tiber melt, and the wide arch

Of the ranged empire fall! Here is my space!

Kingdoms are clay!

(1.1.34–36)

For Rome to “melt is for it to lose its defining shape, the boundary that contains its civic and military

codes. This schema is important in understanding Antony’s grand failure because the Roman container can no longer outline or define him—even to himself. Conversely we come to understand Cleopatra in that the container of her mortality can no longer restrain her. Unlike Antony whose container melts, she gains a sublimity being released into the

air.

In her article “Roman World, Egyptian Earth,” critic Mary Thomas Crane introduces another symbol throughout the play: The four elements. In general, characters associated with Egypt perceive their world composed of the Aristotelian elements, which are earth, wind, fire and water. For Aristotle these physical elements were the centre of the universe and appropriately Cleopatra heralds her coming death when she proclaims, “I am fire and air; my other elements/I give to baser life,”

(5.2.289-90).

Romans, on the other hand, seem to have left behind that system, replacing it with a subjectivity separated from and overlooking the natural world and imagining itself as able to control it. These differing systems of thought and perception result in very different versions of nation and empire. Shakespeare’s relatively positive representation of Egypt has sometimes been read as nostalgia for an heroic past. Because the Aristotelian elements were a declining theory in Shakespeare’s time, it can also be read as nostalgia for a waning theory of the material world, the pre-seventeenth-century cosmos of elements and humors that rendered subject and world deeply interconnected and saturated with

meaning.

Thus this reflects the difference between the Egyptians who are interconnected with the elemental earth and the Romans in their dominating the hard-surfaced, impervious world.

Critics also suggest that the political attitudes of the main characters are an allegory for the political atmosphere of Shakespeare’s time. As a literary device, allegory is essentially an extended metaphor—or a comparison that runs throughout the play. According to Paul Lawrence Rose in his article “The Politics of Antony and Cleopatra," the views expressed in the play of “national solidarity, social order and strong

rule” were familiar after the absolute monarchies of Henry VII and Henry VIII and the political disaster involving Mary Queen of Scots. Essentially the political themes throughout the play are reflective of the different models of rule during Shakespeare’s time. The political attitudes of Antony, Caesar, and Cleopatra are all basic archetypes for the conflicting sixteenth-century views of

kingship.

Caesar is representative of the ideal king, who brings about the Pax Romana similar to the political peace established under the Tudors. His cold demeanour is representative of what the sixteenth century thought to be a side-effect of political genius Conversely, Antony’s focus is on valour and chivalry, and Antony views the political power of victory as a by-product of both. Cleopatra’s power has been described as “naked, hereditary, and

despotic,” and it is argued that she is reminiscent of Mary Tudor’s reign—implying it is not coincidence that she brings about the “doom of Egypt.” This is in part due to an emotional comparison in their rule. Cleopatra, who was emotionally invested in Antony, brought about the downfall of Egypt in her commitment to love, whereas Mary Tudor’s emotional attachment to Catholicism fates her rule. The political implications within the play reflect on Shakespeare’s England in its message that Impact is not a match for

Reason.

The Characterization of Rome and Egypt

Critics have often used the opposition between Rome and Egypt in Antony and Cleopatra to set forth defining characteristics of the various characters. While some characters are distinctly Egyptian others are distinctly Roman, some are torn between the two, and still others attempt to remain

neutral. As critic James Hirsh has stated “as a result, the play dramatizes not two but four main figurative locales: Rome as it is perceived from a Roman point of view; Rome as it is perceived from an Egyptian point of view; Egypt as it is perceived form a Roman point of view; and Egypt as it is perceived from an Egyptian point of

view.:p.175

Rome from the Roman perspective

According to James Hirsh, Rome largely defines itself by its opposition to

Egypt.:p.167-77 Where Rome is viewed as structured, moral, mature, and essentially masculine, Egypt is the polar opposite; chaotic, immoral, immature, and feminine. In fact even the distinction between masculine and feminine is a purely Roman idea which the Egyptians largely ignore. The Romans view the “world” as nothing more than something for them to conquer and control. They believe they are “impervious to environmental

influence” and that they are not to be influenced and controlled by the world but vice versa.

Rome from the Egyptian perspective

The Egyptians view the Romans as boring, oppressive and strict. They lack passion and creativity preferring strict rules and

regulations.:p.177

Egypt from the Egyptian perspective

The Egyptian World view reflects what Mary Floyd-Wilson has called geo-humoralism, or the belief that climate and other environmental factors shapes racial

character. The Egyptians view themselves as deeply entwined with the natural “earth”. Egypt is not a location for them to rule over, but an inextricable part of them. Cleopatra envisions herself as the embodiment of Egypt because she has been nurtured and moulded by the

environment fed by “the dung, / the beggar’s nurse and Caesar’s” (5.2.7-8). They view life as more fluid and less structured allowing for creativity and passionate pursuits.

Egypt from the Roman perspective

The Romans view the Egyptians essentially as improper. Their passion for life is continuously viewed as irresponsible, indulgent, over-sexualized and

disorderly.:p.176-77 The Romans view Egypt as a distraction that can send even the best men off course. This is demonstrated in the following passage describing Antony.

Boys who, being mature in knowledge,

Pawn their experience to their present pleasure,

And so rebel judgment.

(1.4.31-33)

Ultimately the dichotomy between Rome and Egypt is used to distinguish two sets of conflicting values between two different locales. Yet, it goes beyond this division to show the conflicting sets of values not only between two cultures but within cultures, even within

individuals.:p.180 As John Gillies has argued “ the ‘orientalism’ of Cleopatra’s court—with its luxury, decadence, splendour, sensuality, appetite, effeminacy and eunuchs—seems a systematic inversion of the legendary Roman values of temperance, manliness,

courage”. While some characters fall completely into the category of Roman or Egyptian (Octavius as Roman, Cleopatra Egyptian) others, such as Antony, cannot chose between the two conflicting locales and cultures. Instead he oscillates between the two. In the beginning of the play Cleopatra calls attention to this saying

He was dispos’d to mirth, but on the sudden

A Roman thought hath strook him.

(1.2.82-83)

This shows Antony’s willingness to embrace the pleasures of Egyptian life, yet his tendency to still be drawn back into Roman thoughts and ideas.

Thonis-Heracleion was

Egypt’s greatest port for much of the first millennium B.C. before

Alexander the Great established Alexandria in 331 B.C. Then it vanished beneath

the sea in 365 A.D. hiding

the

location of Queen Cleopatra's tomb - a long

lost mystery - until now.

SYNOPSIS

Mark Antony

- one of the triumvirs of the Roman Republic, along with Octavius

and Lepidus

- has neglected his soldierly duties after being beguiled by

Egypt's Queen, Cleopatra. He ignores Rome's domestic problems, including

the fact that his third wife Fulvia rebelled against Octavius and then

died.

Octavius calls Antony back to Rome from Alexandria to help him fight against Sextus Pompey, Menecrates, and Menas, three notorious pirates of the

Mediterranean. At

Alexandria, Cleopatra begs Antony not to go, and though he repeatedly affirms his deep passionate love for her, he eventually leaves.

The triumvirs meet in Rome, where Antony and Octavius put to rest,

for now, their disagreements. Octavius' general, Agrippa, suggests that

Antony should marry Octavius's sister, Octavia, in order to cement the

friendly bond between the two men. Antony accepts. Antony's lieutenant

Enobarbus, though, knows that Octavia can never satisfy him after

Cleopatra. In a famous passage, he describes Cleopatra's charms: "Age

cannot wither her, nor custom stale / Her infinite variety: other women

cloy / The appetites they feed, but she makes hungry / Where most she

satisfies."

A soothsayer warns Antony that he is sure to lose if he ever tries to fight Octavius.

In Egypt, Cleopatra learns of Antony's marriage to Octavia and

takes furious revenge upon the messenger who brings her the news. She

grows content only when her courtiers assure her that Octavia is homely:

short, low-browed, round-faced and with bad hair.

Before battle, the triumvirs parley with Sextus Pompey, and offer

him a truce. He can retain Sicily and Sardinia, but he must help them

"rid the sea of pirates" and send them tributes. After some hesitation,

Sextus agrees. They engage in a drunken celebration on Sextus' galley,

though the austere Octavius leaves early and sober from the party. Menas

suggests to Sextus that he kill the three triumvirs and make himself

ruler of the Roman Republic, but he refuses, finding it dishonourable.

After Antony departs Rome for Athens, Octavius and Lepidus break their

truce with Sextus and war against him. This is unapproved by Antony, and

he is furious.

Antony returns to Hellenistic Alexandria and crowns Cleopatra and himself as rulers of

Egypt

and the eastern third of the Roman Republic (which was Antony's share

as one of the triumvirs). He accuses Octavius of not giving him his fair

share of Sextus' lands, and is angry that Lepidus, whom Octavius has

imprisoned, is out of the triumvirate. Octavius agrees to the former

demand, but otherwise is very displeased with what Antony has

done.

Antony prepares to battle Octavius. Enobarbus urges Antony to

fight on land, where he has the advantage, instead of by sea, where the

navy of Octavius is lighter, more mobile and better manned. Antony

refuses, since Octavius has dared him to fight at sea. Cleopatra pledges

her fleet to aid Antony. However, during the

Battle of Actium

off the western coast of Greece, Cleopatra flees with her sixty ships,

and Antony follows her, leaving his forces to ruin. Ashamed of what he

has done for the love of Cleopatra, Antony reproaches her for making him

a coward, but also sets this true and deep love above all else, saying

"Give me a kiss; even this repays me."

Octavius sends a messenger to ask Cleopatra to give up Antony and

come over to his side. She hesitates, and flirts with the messenger,

when Antony walks in and angrily denounces her behavior. He sends the

messenger to be whipped. Eventually, he forgives Cleopatra and pledges

to fight another battle for her, this time on land.

On the eve of the battle, Antony's soldiers hear strange portents,

which they interpret as the god Hercules abandoning his protection of

Antony. Furthermore, Enobarbus, Antony's long-serving lieutenant,

deserts him and goes over to Octavius' side. Rather than confiscating

Enobarbus' goods, which Enobarbus did not take with him when he fled,

Antony orders them to be sent to Enobarbus. Enobarbus is so overwhelmed

by Antony's generosity, and so ashamed of his own disloyalty, that he

dies from a broken heart.

Antony loses the battle as his troops desert en masse and he denounces Cleopatra: "This foul Egyptian hath betrayed me." He resolves to kill her for the imagined treachery.

Cleopatra

decides that the only way to win back Antony's love is to send him word

that she killed herself, dying with his name on her lips. She locks

herself in her monument, and awaits Antony's return.

Her plan backfires: rather than rushing back in remorse to see the

"dead" Cleopatra, Antony decides that his own life is no longer worth

living. He begs one of his aides, Eros, to run him through with a sword,

but Eros cannot bear to do it and kills himself. Antony admires Eros'

courage and attempts to do the same, but only succeeds in wounding

himself. In great pain, he learns that Cleopatra is indeed alive. He is

hoisted up to her in her monument and dies in her arms.

Since Egypt has been defeated, the captive Cleopatra is placed under a guard of

Roman soldiers. She tries to take her own life with a dagger, but Proculeius disarms her.

Octavius

arrives, assuring her she will be treated with honour and dignity. But

Dolabella secretly warns her that Octavius intends to parade her at his

Roman triumph. Cleopatra bitterly envisions the endless humiliations

awaiting her for the rest of her life as a Roman conquest.

Cleopatra kills herself using the venomous bite of an asp,

imagining how she will meet Antony again in the afterlife. Her serving

maids Iras and Charmian also die, Iras from heartbreak and Charmian from

one of the two asps in Cleopatra's basket. Octavius discovers the dead

bodies and experiences conflicting emotions. Antony and Cleopatra's

deaths leave him free to become the first Roman Emperor, but he also

feels some sympathy for them. He orders a public military funeral.

ACT

I

SCENE

I. Alexandria. A

room in CLEOPATRA's palace.

SCENE

II. The same. Another

room. Enter CHARMIAN, IRAS, ALEXAS, and a Soothsayer

SCENE

III. The same. Another

room. Enter CLEOPATRA, CHARMIAN, IRAS, and ALEXAS

SCENE

IV. Rome. OCTAVIUS CAESAR's house. Enter OCTAVIUS CAESAR, reading

a letter, LEPIDUS, and their Train

SCENE

V. Alexandria. CLEOPATRA's palace. Enter CLEOPATRA, CHARMIAN,

IRAS, and MARDIAN

ACT II

SCENE

I. Messina. POMPEY's house. Enter POMPEY, MENECRATES, and

MENAS, in warlike manner

SCENE

II. Rome. The house of LEPIDUS. Enter

DOMITIUS ENOBARBUS and LEPIDUS

SCENE

III. The same. OCTAVIUS CAESAR's house. Enter MARK ANTONY, CAESAR,

OCTAVIA between them, and Attendants

SCENE

IV.

Lepidus sets off to do battle with Pompey.

Urging Maecenas and Agrippa hasten departures of Antony and Caesar.

SCENE

V. Alexandria. CLEOPATRA's palace. Enter

CLEOPATRA, CHARMIAN, IRAS, and ALEXAS

SCENE

VI. Near Misenum. Enter Pompey, Menas drum/trumpet Caesar,

Antony, Lepidus, Enobarbus, Mecaenas, Soldiers

SCENE

VII. On board POMPEY's galley, off Misenum. Music plays.

Enter two or three Servants with a banquet

ACT III

SCENE

I. A plain in Syria. Enter VENTIDIUS in triumph, with SILIUS,

Romans, Officers, Soldiers; the body of PACORUS before him

SCENE

II. Rome. An ante-chamber in OCTAVIUS CAESAR's house. Enter AGRIPPA

one door, DOMITIUS ENOBARBUS another

SCENE

III. Alexandria. CLEOPATRA's palace. Enter CLEOPATRA, CHARMIAN,

IRAS, and ALEXAS

SCENE

IV. Athens. A room in MARK ANTONY's house. Enter MARK ANTONY

and OCTAVIA

SCENE

V. The same. Another room. Enter DOMITIUS ENOBARBUS and

EROS, meeting

SCENE

VI. Rome. OCTAVIUS CAESAR's house. Enter OCTAVIUS CAESAR,

AGRIPPA, and MECAENAS

SCENE

VII. Near Actium. MARK ANTONY's camp. Enter CLEOPATRA and DOMITIUS

ENOBARBUS

SCENE

VIII. A plain near Actium. Enter OCTAVIUS CAESAR, and

TAURUS, with his army, marching

SCENE

IX. Another part of the plain. Enter MARK ANTONY and

DOMITIUS ENOBARBUS

SCENE

X. Another part of the plain. CANIDIUS marcheth; and TAURUS,

lieutenant CAESAR, heard the noise of a sea-fight

SCENE

XI. Alexandria. CLEOPATRA's palace. Enter MARK ANTONY with

Attendants

SCENE

XII. Egypt. OCTAVIUS CAESAR's camp. Enter OCTAVIUS CAESAR,

DOLABELLA, THYREUS, with others

SCENE

XIII. Alexandria. CLEOPATRA's palace. Enter CLEOPATRA,

DOMITIUS ENOBARBUS, CHARMIAN, and IRAS

ACT IV

SCENE

I. Before Alexandria. OCTAVIUS CAESAR's camp. Enter Caesar,

Agrippa, Mecaenas, with Army; Caesar reading a letter

SCENE

II. Alexandria. CLEOPATRA's palace. Enter ANTONY, CLEOPATRA,

ENOBARBUS, CHARMIAN, IRAS, ALEXAS, with others

SCENE

III. The same. Before the palace. Enter two Soldiers to

their guard

SCENE

IV. The same. A room in the palace. Enter MARK ANTONY and

CLEOPATRA, CHARMIAN, and others attending

SCENE

V. Alexandria. MARK ANTONY's camp. Trumpets sound. Enter MARK

ANTONY and EROS; a Soldier meeting them

SCENE

VI. Alexandria. OCTAVIUS CAESAR's camp. Enter OCTAVIUS CAESAR,

AGRIPPA, with DOMITIUS ENOBARBUS, and others

SCENE

VII. Field of battle between the camps. Alarum. Drums and trumpets.

Enter AGRIPPA and others

SCENE

VIII. Under the walls of Alexandria. Alarum. Enter MARK ANTONY, in

a march; SCARUS, with others

SCENE

IX. OCTAVIUS CAESAR's camp. Sentinels at their post

SCENE

X. Between the two camps. Enter MARK ANTONY and SCARUS, with their

Army

SCENE

XI. Another part of the same. Enter OCTAVIUS CAESAR, and his

Army

SCENE

XII. Another part of the same. Enter MARK ANTONY and SCARUS

SCENE

XIII. Alexandria. Cleopatra's palace. Enter CLEOPATRA, CHARMIAN,

IRAS, and MARDIAN

SCENE

XIV. The same. Another room. Enter MARK ANTONY and EROS

SCENE

XV. The same. A monument. Enter CLEOPATRA and her maids aloft,

with CHARMIAN and IRAS

ACT V

SCENE

I. Alexandria. OCTAVIUS CAESAR's camp. Enter Octavius, Agrippa,

Dolabella, Maceanas, Gallus, Proculeius, council of war

SCENE

II. Alexandria. A room in the monument. Enter CLEOPATRA, CHARMIAN,

and IRAS Queen's suicide by poison asps

LINKS:

Smooth

Faced Gentlemen - An all female Troupe producing quality productions

of Shakespeare's plays.

No

Fear Shakespeare: the text of the play with a glossary

Cleopatra

on the Web, particularly the Antony

and Cleopatra section

The

Tragedie of Anthonie and Cleopatra – HTML version of this title.

Antony

and Cleopatra – Full text HTML of the play

Full

text of play

Antony

And Cleopatra – plain vanilla text from Project Gutenberg

Antony

and Cleopatra – Scene-indexed and searchable version of the play.

Antony

and Cleopatra study guide, themes, quotes, character analyses,

teaching guide

Joyce

Carol Oates on Antony and Cleopatra

Wikipedia

Egypt

- Google Maps

Antony

and Cleopatra * Hamlet

* Macbeth * Othello * Romeo

and Juliet

A

Midsummer Night's Dream * As

You Like It * Much Ado About Nothing

The

Merchant of Venice * The Taming of the Shrew

Ashlea

* Camina

* Carly * Fran

* Henri * Kayleigh

* Leila * Mariam

History

becomes too real for comfort

for

an archaeological

expedition

|