|

Titus Andronicus is a tragedy by William Shakespeare, and possibly George Peele, believed to have been written between 1588 and 1593. It is thought to be

Shakespeare's first tragedy, and is often seen as his attempt to emulate the violent and bloody revenge plays of his contemporaries, which were extremely popular with audiences throughout the sixteenth century.

The play is set during the latter days of the Roman Empire and tells the fictional story of Titus, a general in the Roman army, who is engaged in a cycle of revenge with Tamora, Queen of the Goths. It is Shakespeare's bloodiest and most violent work and traditionally was one of his least respected plays. Although it was extremely popular in its day, it fell out of favour during the Victorian era, primarily because of what was considered to be a distasteful use of graphic violence, but from around the middle of the twentieth century its reputation began to improve.

CHARACTERS

Titus Andronicus – renowned Roman general

Lucius – Titus's eldest son

Quintus – Titus's son

Martius – Titus's son

Mutius – Titus's son

Young Lucius – Lucius's son and Titus' grandson

Lavinia – Titus's daughter

Marcus Andronicus – Titus's brother and tribune to the people of Rome

Publius – Marcus's son

Saturninus – Son of the late Emperor of Rome; afterwards declared Emperor

Bassianus – Saturninus's brother; in love with Lavinia

Sempronius – Titus's kinsman (non-speaking role)

Caius – Titus's kinsman (non-speaking role)

Valentine – Titus's kinsman (non-speaking role)

Æmilius – Roman noble

Tamora – Queen of the Goths; afterwards Empress of Rome

Demetrius – Tamora's son

Chiron – Tamora's son

Alarbus – Tamora's son (non-speaking role)

Aaron – a Moor; involved in a sexual relationship with Tamora

Nurse

Clown

Messenger

Roman Captain

First Goth

Second Goth

Senators, Tribunes, Soldiers, Plebians, Goths etc.

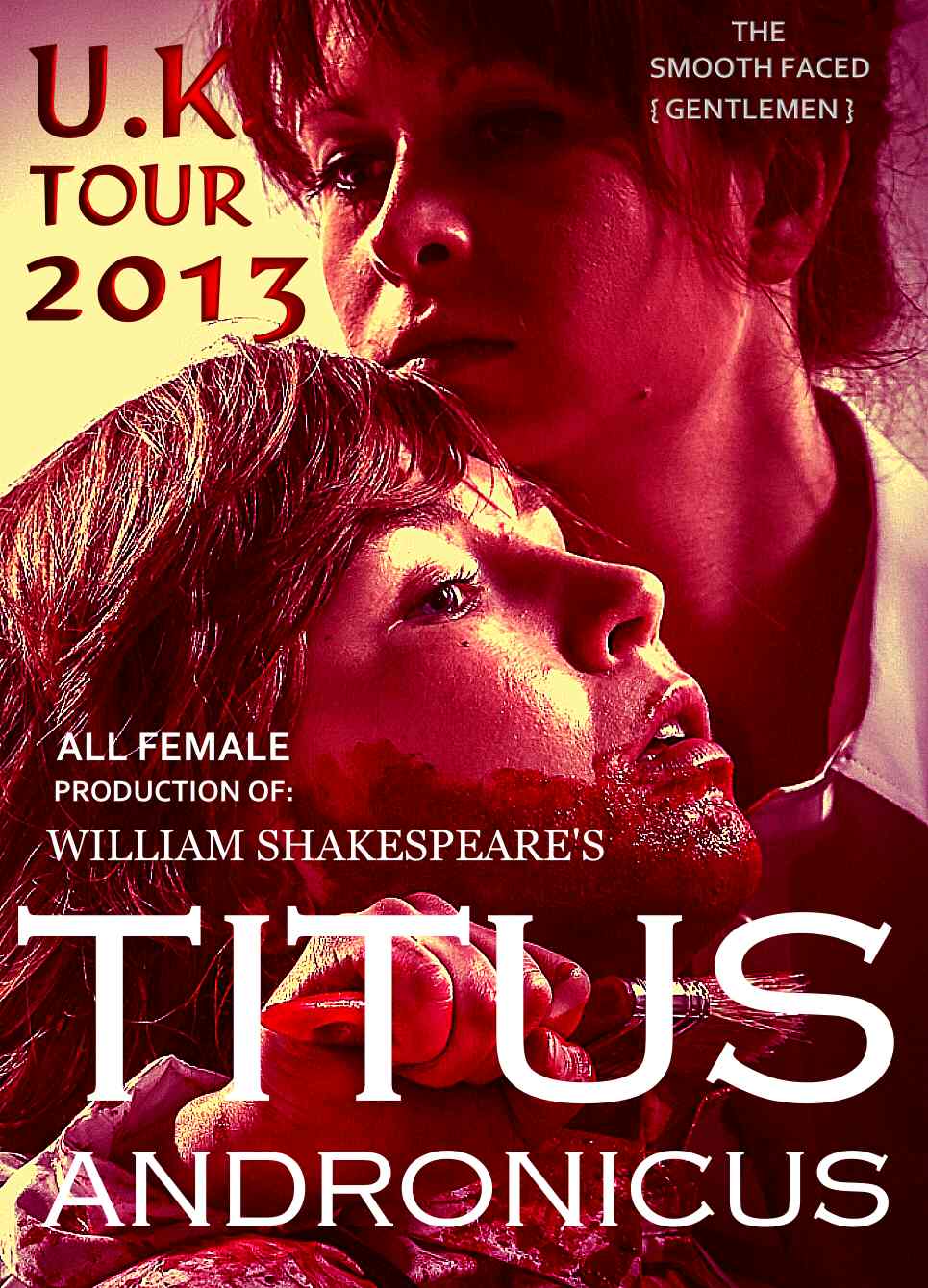

The

all female cast of Titus Andronicus (minus Emma Nixon) outside the Greenwich Theatre,

London, England 2015.

2013

THE

SMOOTH FACED PLAYERS: TITUS ANDRONICUS CAST - In alphabetical order

|

|

|

|

|

|

Vivienne

Acheampong |

Fran

Binefa |

Madeline Gould |

Ashlea

Kaye |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Henri

Merriam |

Emma

Nixon |

Leila

Sykes |

Stella Taylor |

SYNOPSIS

The play begins shortly after the death of the Roman Emperor, with his two sons, Saturninus and Bassianus, squabbling over who will succeed him. Their conflict seems set to boil over into violence until a tribune, Marcus Andronicus, announces that the people's choice for the new emperor is his brother, Titus, who will shortly return to Rome from a victorious ten-year campaign against the Goths. Titus subsequently arrives to much fanfare, bearing with him as prisoners the Queen of the Goths (Tamora), her three sons, and Aaron the Moor (her secret lover). Despite the desperate pleas of Tamora, Titus sacrifices her eldest son, Alarbus, in order to avenge the deaths of his own sons during the war. Distraught, Tamora and her two surviving sons, Demetrius and Chiron, vow revenge on Titus and his family.

Meanwhile, Titus refuses the offer of the throne, arguing that he is not fit to rule, and instead supporting Saturninus' claim, who is duly elected. Saturninus tells Titus that for his first act as Emperor, he will marry Titus's daughter Lavinia. Titus agrees, although Lavinia is already betrothed to Bassianus, who refuses to give her up. Titus's sons tell Titus that Bassianus is in the right under Roman law, but Titus refuses to listen, accusing them all of treason. A scuffle breaks out, during which Titus kills his own son, Mutius. Saturninus then denounces the Andronicus family for their effrontery and shocks Titus by marrying Tamora. However, putting into motion her plan for revenge, Tamora advises Saturninus to pardon Bassianus and the Andronicus family, which he reluctantly does.

During a royal hunt the following day, Tamora persuades Demetrius and Chiron to kill Bassianus, so they may rape Lavinia. They do so, throwing Bassianus' body into a pit, and dragging Lavinia deep into the forest before violently raping her. To keep her from revealing what has happened, they cut out her tongue and cut off her hands. Meanwhile, Aaron frames Titus's sons Martius and Quintus for the murder of Bassianus with a forged letter. Horrified at the death of his brother, Saturninus arrests Martius and Quintus and sentences them to death.

Some time later, Marcus discovers the mutilated Lavinia and takes her to her father, who is still shocked at the accusations levelled at his sons, and upon seeing Lavinia, is overcome with grief. Aaron then visits Titus, falsely telling him that Saturninus will spare Martius and Quintus if either Titus, Marcus or, Titus's remaining son, Lucius, cuts off one of their hands and sends it to him. Titus has Aaron cut off his hand and send it to the emperor, but in return, a messenger brings Titus Martius and Quintus' severed heads, along with Titus's severed left hand. Desperate for revenge, Titus orders Lucius to flee Rome and raise an army among their former enemy, the Goths.

Later, Lavinia 'writes' the names of her attackers in the dirt, using a stick held with her mouth and between her stumps. Meanwhile, Tamora secretly gives birth to a mixed-race child, fathered by Aaron. Aaron kills the midwife and nurse and flees with the baby to save it from Saturninus' inevitable wrath. Thereafter, Lucius, marching on Rome with an army, captures Aaron and threatens to hang the infant. To save the baby, Aaron reveals the entire revenge plot to Lucius.

Back in Rome, Titus's behaviour suggests he may have gone insane. Convinced of his madness, Tamora, Chiron and Demetrius approach him, dressed as the spirits of Revenge, Murder, and Rape. Tamora (as Revenge) tells Titus that she will grant him revenge on all of his enemies if he can convince Lucius to postpone the imminent attack on Rome. Titus agrees and sends Marcus to invite Lucius to a reconciliatory feast. Revenge then offers to invite the Emperor and Tamora as well, and is about to leave when Titus insists that Rape and Murder (Chiron and Demetrius) stay with him. When Tamora is gone, Titus cuts their throats and drains their blood into a basin held by Lavinia. Titus morbidly tells Lavinia that he plans to "play the cook" and grind the bones of Demetrius and Chiron into powder and bake their heads.

The next day, during the feast at his house, Titus asks Saturninus if a father should kill his daughter when she has been raped. When Saturninus answers that he should, Titus kills Lavinia, telling Saturninus of the rape. When the Emperor calls for Chiron and Demetrius, Titus reveals that they have been baked in the pie Tamora has just been eating. Titus then kills Tamora, and is immediately killed by Saturninus, who is subsequently killed by Lucius to avenge his father's death. Lucius is then proclaimed Emperor. He orders that Saturninus be given a state burial, that Tamora's body be thrown to the wild beasts outside the city, and that Aaron be buried chest-deep and left to die of thirst and starvation. Aaron, however, is unrepentant to the end, regretting only that he had not done more evil in his life.

Sources

The story of Titus Andronicus is fictional, not historical, unlike Shakespeare's other Roman plays, Julius Caesar, Antony and Cleopatra and Coriolanus, all of which are based on real historical events and people. Even the time in which Titus is set may not be based on a real historical period. According to the prose version of the play (see below), the events are "set in the time of Theodosius", who ruled from 379 to 395. On the other hand, the general setting appears to be what Clifford Huffman describes as "late-Imperial Christian Rome," possibly during the reign of Justinian I (527–565). Also favouring a later date, Grace Starry West argues, "the Rome of Titus Andronicus is Rome after Brutus, after Caesar, and after Ovid. We know it is a later Rome because the emperor is routinely called Caesar; because the characters are constantly alluding to Tarquin, Lucretia, and Brutus, suggesting that they learned about Brutus' new founding of Rome from the same literary sources we do, Livy and Plutarch." Others are less certain of a specific setting however. For example, Jonathan Bate has pointed out that the play begins with Titus returning from a successful ten-year campaign against the Goths, as if at the height of the Roman Empire, but ends with Goths invading Rome, as if at its death. Similarly, T.J.B. Spencer argues that "the play does not assume a political situation known to Roman history; it is, rather a summary of Roman politics. It is not so much that any particular set of political institutions is assumed in Titus, but rather that it includes all the political institutions that Rome ever had."

In his efforts to fashion general history into a specific fictional story, Shakespeare may have consulted the Gesta Romanorum, a well known thirteenth-century collection of tales, legends, myths and anecdotes in Latin, which took figures and events from history and spun fictional tales around them. In Shakespeare's own lifetime, a writer known for doing likewise was Matteo Bandello, who based his work on that of writers such as Giovanni Boccaccio and Geoffrey Chaucer, and who could have served as an indirect source for Shakespeare. So too could the first major English author to write in this style, William Painter, who borrowed from, amongst others, Herodotus, Plutarch, Aulus Gellius, Claudius Aelianus, Livy, Tacitus, Giovanni Battista Giraldi, and Bandello himself. The possibility that Shakespeare may have used the Gesta, Bandello and/or Painter is strengthened by the fact that he definitely consulted all three sources later in his career; the Gesta provided some of the details for King Lear, Bandello was the primary source for Twelfth Night, and Painter was used during the composition of All's Well That Ends Well.

However, it is also possible to determine more specific sources for the play. The primary source for the rape and mutilation of Lavinia, as well as Titus' subsequent revenge, is Ovid's Metamorphoses (c.AD 8), which is featured in the play itself when Lavinia uses it to help explain to Titus and Marcus what happened to her during the attack. In the sixth book of Metamorphoses, Ovid tells the story of the rape of Philomela, daughter of Pandion I, King of Athens. Despite ill omens, Philomela's sister, Procne, marries Tereus of Thrace and has a son for him, Itys. After five years in Thrace, Procne yearns to see her sister again, so she persuades Tereus to travel to Athens and accompany Philomela back to Thrace. Tereus does so, but he soon begins to lust after Philomela. When she refuses his advances, he drags her into a forest and rapes her. He then cuts out her tongue to prevent her telling anyone of the incident and returns to Procne, telling her that Philomela is dead. However, Philomela weaves a tapestry in which she names Tereus as her assailant, and has it sent to Procne. The sisters meet in the forest and together they plot their revenge. They kill Itys and cook his body in a pie, which Procne then serves to Tereus. During the meal, Philomela reveals herself, showing Itys' head to Tereus and telling him what they have done.

For the scene where Lavinia reveals her rapists by writing in the sand, Shakespeare may have used a story from the first book of Metamorphoses; the tale of the rape of Io by Zeus, where, to prevent her divulging the story, he turns her into a cow. Upon encountering her father, she attempts to tell him who she is, but is unable to do so until she thinks to scratch her name in the dirt using her hoof.

Titus' revenge may also have been influenced by Seneca's play Thyestes, written in the first century AD. The play tells the story of Thyestes, son of Pelops, King of Pisa, who, along with his brother Atreus, was exiled by Pelops for the murder of their half-brother, Chrysippus. They take up refuge in Mycenae, and soon ascend to co-inhabit the throne. However, each becomes jealous of the other, and Thyestes tricks Atreus into electing him as the sole king. Determined to re-attain the throne, Atreus enlists the aid of Zeus and Hermes, and has Thyestes banished from Mycenae. Atreus subsequently discovers that his wife, Aerope, had been having an affair with Thyestes, and he vows revenge. He asks Thyestes to return to Mycenae with his family, telling him that all past animosities are forgotten. However, when Thyestes returns, Atreus secretly kills Thyestes' sons, Pelopia and Aegisthus. He cuts off their hands and heads and cooks the rest of their bodies in a pie. At a reconciliatory feast, Atreus serves Thyestes the pie in which his sons have been baked. As Thyestes finishes his meal, Atreus produces the hands and heads, revealing to the horrified Thyestes what he has done.

Another specific source for the final scene is discernible when Titus asks Saturninus if a father should kill his daughter when she has been raped. This is a reference to the story of Verginia from Livy's Ab urbe condita (c.26 B.C.). Around 451 B.C., a decemvir of the Roman Republic, Appius Claudius Crassus begins to lust after Verginia, a plebeian girl betrothed to a former tribune, Lucius Icilius. She rejects Claudius' advances, enraging him, and he has her abducted. However, both Icilius and Verginia's father, famed centurion Lucius Verginius, are respected figures and Claudius is forced to legally defend his right to hold Verginia. At the Forum, Claudius threatens the assembly with violence and Verginius' supporters flee. Seeing that defeat is immanent, Verginius asks Claudius if he may speak to his daughter alone, to which Claudius agrees. However, Verginius stabs Verginia, determining that her death is the only way he can secure her freedom.

For the scene where Aaron tricks Titus into cutting off one of his hands, the primary source was probably an unnamed popular tale about a Moor's vengeance, published in various languages throughout the sixteenth century (an English version entered into the Stationers' Register in 1569 has not survived). In the story, a married noble man with two children chastises his Moorish servant, who vows revenge. The servant goes to the moated tower where the man's wife and children live, and rapes the wife. Her screams bring her husband, but the Moor pulls up the drawbridge before he can gain entry. The Moor then kills both children on the battlements in full view of the man. He pleads with the Moor that he will do anything to save his wife, and the Moor demands he cut off his nose. The man does so, but the Moor kills the wife anyway and the man dies of shock. The Moor then flings himself from the battlements to avoid punishment.

Shakespeare also drew on various sources for the names of many of his characters. For example, Titus could have been named after the Emperor Titus Flavius Vespasianus, who ruled Rome from 79 to 81. Jonathan Bate speculates that the name Andronicus could have come from Andronicus V Palaeologus, co-emperor of Byzantium from 1403 to 1407, but, since there is no reason to suppose that Shakespeare might have come across these emperors, it is more likely that he took the name from the story "Andronicus and the lion" in Antonio de Guevara's Epistolas familiares. That story involves a sadistic emperor named Titus who amused himself by throwing slaves to wild animals and watching them be slaughtered. However, when a slave called Andronicus is thrown to a lion, the lion lies down and embraces the man. The emperor demands to know what has happened, and Andronicus explains that he had once helped the lion by removing a thorn from its foot. Bate speculates that this story, with one character called Titus and another called Andronicus, could be why several contemporary references to the play are in the form Titus & ondronicus.

Geoffrey Bullough argues that Lucius' character arc (estrangement from his father followed by banishment followed by a glorious return to avenge his family honour) was probably based on Plutarch's Life of Coriolanus. As for Lucius' name, Frances Yates speculates that he may be named after Saint Lucius, who introduced Christianity into Britain. On the other hand, Jonathan Bate hypothesises that Lucius could be named after Lucius Junius Brutus, founder of the Roman Republic, arguing that "the man who led the people in their uprising was Lucius Junius Brutus. This is the role that Lucius fulfils in the play."

The name of Lavinia was probably taken from the mythological figure of Lavinia, daughter of Latinus, King of Latium, who, in Virgil's Aeneid, courts Aeneas as he attempts to settle his people in Latium. A.C. Hamilton speculates that the name of Tamora could have been based upon the historical figure of Tomyris, a violent and uncompromising Massagetae queen. Eugene M. Waith suggests that the name of Tamora's son, Alarbus, could have come from George Puttenham's The Arte of English Poesie (1589), which contains the line "the Roman prince did daunt/Wild Africans and the lawless Alarbes." G.K. Hunter has suggested Shakespeare may have taken Saturninus' name from Herodian's History of the Empire from the Death of Marcus, which features a jealous and violent tribune named Saturninus. On the other hand, Waith speculates that Shakespeare may have been thinking of an astrological theory which he could have seen in Guy Marchant's The Kalendayr of the shyppars (1503), which states that Saturnine men (i.e. men born under the influence of Saturn) are "false, envious and malicious."

Shakespeare most likely took the names of Bassianus, Marcus, Martius, Quintus, Cauis, Æmilius, Demetrius and Sempronius from Plutarch's Life of Scipio Africanus. Bassianus' name probably came from Lucius Septimius Bassianus, better known as Caracalla, a major figure in Africanus, who, like Bassianus in the play, fights with his brother over succession, one appealing to primogeniture and the other to popularity.

The ballad and the prose history

Any discussion of the sources of Titus Andronicus is complicated by the existence of two other versions of the story; a prose history and a ballad (both of which are anonymous and undated).

The first definite reference to the ballad, Titus Andronicus' Complaint, is an entry in the Stationers' Register by the printer John Danter on 6 February 1594, where the entry "A booke intitled a Noble Roman Historye of Tytus Andronicus" is immediately followed by "Entred also vnto him, the ballad thereof". The earliest surviving copy of the ballad is in Richard Johnson's The Golden Garland of Princely Pleasures and Delicate Delights (1620). However, the date of composition is unknown.

The prose was first published in chapbook form some time between 1736 and 1764 by Cluer Dicey under the title The History of Titus Andronicus, the Renowned Roman General (the ballad was also included in the chapbook), however it is believed to be much older than that. The copyright records from the Stationers' Register in Shakespeare's own lifetime provide some tenuous evidence regarding the dating of the prose. On 19 April 1602, the publisher Thomas Millington sold his share in the copyright of "A booke intitled a Noble Roman Historye of Tytus Andronicus" (which Danter had initially entered into the Register in 1594) to Thomas Pavier. The orthodox belief is that this entry refers to the play. However, the next version of the play to be published was for Edward White, in 1611, printed by Edward Allde, thus prompting the question of why Pavier never published the play despite owning the copyright for nine years. Joseph Quincy Adams, Jr. believes that the original Danter entry in 1594 is not a reference to the play but to the prose, and the subsequent transferrals of copyright relate to the prose, not the play, thus explaining why Pavier never published the play. Similarly, W.W. Greg believes that all copyright to the play lapsed upon Danter's death in 1600, hence the 1602 transferral from Millington to Pavier was illegitimate unless it refers to something other than the play; i.e. the prose. Both scholars conclude that the evidence seems to imply the prose existed by early 1594 at the latest.

However, even if the prose was in existence by 1594, there is no solid evidence to suggest the order in which the play, ballad and prose were written and which served as source for which. Traditionally, the prose has been seen as the original, with the play derived from it, and the ballad derived from both play and prose. Adams Jr., for example, firmly believed in this order (prose-play-ballad) as did John Dover Wilson and Geoffrey Bullough. This theory is by no means universally accepted however. For example, Ralph M. Sargent agrees with Adams and Bullough that the prose was the source of the play, but he argues that the poem was also a source of the play (prose-ballad-play). On the other hand, Marco Mincoff rejects both theories, arguing instead that the play came first, and served as a source for both the ballad and the prose (play-ballad-prose). G. Harold Metz felt that Mincoff was incorrect and reasserted the primacy of the prose-play-ballad sequence. G.K. Hunter however, believes that Adams, Dover Wilson, Bullough, Sargent, Mincoff and Metz were all wrong, and the play was the source for the prose, with both serving as sources for the ballad (play-prose-ballad). In his 1984 edition of the play for The Oxford Shakespeare, Eugene M. Waith rejects Hunter's theory and supports the original prose-play-ballad sequence. On the other hand, in his 1995 edition for the Arden Shakespeare 3rd Series, Jonathan Bate favours Mincoff's theory of play-ballad-prose. In the introduction to the 2001 edition of the play for the Penguin Shakespeare (edited by Sonia Massai), Jacques Berthoud agrees with Waith and settles on the initial prose-play-ballad sequence. In his 2006 revised edition for the New Cambridge Shakespeare, Alan Hughes also argues for the original prose-play-ballad theory, but hypothesises that the source for the ballad was exclusively the prose, not the play.

Ultimately, there is no overriding critical consensus on the issue of the order in which the play, prose and ballad were written, with the only tentative agreement being that all three were probably in existence by 1594 at the latest.

PERFORMANCE

The earliest definite recorded performance of Titus was on 24 January 1594, when Philip Henslowe noted a performance by Sussex's Men of Titus & ondronicus. Although Henslowe doesn't specify a theatre, it was most likely The Rose. Repeated performances were staged on 28 January and 6 February. On 5 and 12 June, Henslowe recorded two further performances of the play, at the Newington Butts Theatre by the combined Admiral's Men and Lord Chamberlain's Men. The 24 January show earned three pounds eight shillings, and the performances on 29 January and 6 February earned two pounds each, making it the most profitable play of the season. The next recorded performance was on 1 January 1596, when a troupe of London actors, possibly Chamberlain's Men, performed the play during the Christmas festivities at Burley-on-the-Hill in the manor of Sir John Harington, Baron of Exton.

Some scholars, however, have suggested that the January 1594 performance may not be the first recorded performance of the play. On 11 April 1592, Henslowe recorded ten performances by Derby's Men of a play called Titus and Vespasian, which some, such as E.K. Chambers, have identified with Shakespeare's play. Most scholars, however, believe that Titus and Vespasian is more likely a different play about the two real life Roman Emperors, Vespasian, who ruled from 69 to 79, and his son Titus, who ruled from 79 to 81. The two were subjects of many narratives at the time, and a play about them would not have been unusual. Dover Wilson further argues that the theory that Titus and Vespasian is Titus Andronicus probably originated in an 1865 English translation of a 1620 German translation of Titus, in which Lucius had been renamed Vespasian.

Although it is known that the play was definitely popular in its day, there is no other recorded performance for many years. In January 1668, it was listed by the Lord Chamberlain as one of twenty-one plays owned by the King's Company which had, at some stage previously, been acted at Blackfriars Theatre; "A Catalogue of part of his Mates Servants Playes as they were formally acted at the Blackfryers & now allowed of to his Mates Servants at ye New Theatre." However, no other information is provided. During the late seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, adaptations of the play came to dominate the stage, and after the Burley performance in 1596 and the possible Blackfriars performance some time prior to 1667, there is no definite recorded performance of the Shakespearean text in England until the early twentieth century.

After over 300 years absent from the English stage, the play returned on 8 October 1923, in a production directed by Robert Atkins at The Old Vic, as part of the Vic's presentation of the complete dramatic works over a seven-year period. The production featured Wilfred Walter as Titus, Florence Saunders as Tamora, George Hayes as Aaron and Jane Bacon as Lavinia. Reviews at the time praised Hayes' performance but criticised Walter's as monotonous. Atkins staged the play with a strong sense of Elizabethan theatrical authenticity, with a plain black backdrop, and a minimum of props. Critically, the production met with mixed reviews, some welcoming the return of the original play to the stage, some questioning why Atkins had bothered when various adaptations were much better and still extant. Nevertheless, the play was a huge box office success, one of the most successful in the Complete Works presentation.

The earliest known performance of the Shakespearean text in the United States was in April 1924 when the Alpha Delta Phi fraternity of Yale University staged the play under the direction of John M. Berdan and E.M. Woolley as part of a double bill with Robert Greene's Friar Bacon and Friar Bungay. Whilst some material was removed from 3.2, 3.3 and 3.4, the rest of the play was left intact, with much attention devoted to the violence and gore. The cast list for this production has been lost.

The best known and most successful production of the play in England was directed by Peter Brook for the RSC at the Royal Shakespeare Theatre in 1955, starring Laurence Olivier as Titus, Maxine Audley as Tamora, Anthony Quayle as Aaron and Vivien Leigh as Lavinia. Brook had been offered the chance to direct Macbeth but had controversially turned it down, and instead decided to stage Titus. The media predicted that the production would be a massive failure, and possibly spell the end of Brook's career, but on the contrary, it was a huge commercial and critical success, with many of the reviews arguing that Brook's alterations improved Shakespeare's script (Marcus' lengthy speech upon discovering Lavinia was removed and some of the scenes in Act 4 were reorganised). Olivier in particular was singled out for his performance and for making Titus a truly sympathetic character. J.C. Trewin for example, wrote "the actor had thought himself into the hell of Titus; we forgot the inadequacy of the words in the spell of the projection." The production is also noted for muting the violence; Chiron and Demetrius were killed off stage; the heads of Quintus and Mutius were never seen; the nurse is strangled, not stabbed; Titus' hand was never seen; blood and wounds were symbolised by red ribbons. Edward Trostle Jones summed up the style of the production as employing "stylised distancing effects." The scene where Lavinia first appears after the rape was singled out by critics as being especially horrific, with her wounds portrayed by red streamers hanging from her wrists and mouth. Some reviewers however, found the production too beautified, making it unrealistic, with several commenting on the cleanness of Lavinia's face after her tongue has supposedly been cut out. After its hugely successful Royal Shakespeare Theatre run, the play went on tour around Europe. No video recordings of the production are known, although there are many photographs available.

The success of the Brook production seems to have provided an impetus for directors to tackle the play, and ever since 1955, there has been a steady stream of performances on the English and American stages. After Brook, the next major production came in 1967, when Douglas Seale directed an extremely graphic and realistic presentation at the Centre Stage in Baltimore with costumes that recalled the various combatants in World War II. Seale's production employed a strong sense of realism to make parallels between the contemporary period and that of Titus, and thus comment on the universality of violence and revenge. Seale set the play in the 1940s and made pointed parallels with concentration camps, the massacre at Katyn, the Nuremberg Rallies and the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings. Saturninus was based on Benito Mussolini and all his followers dressed entirely in black; Titus was modelled after a Prussian Army officer; the Andronici wore Nazi insignia and the Goths at the end of the play were dressed in Allied Forces uniforms; the murders in the last scene are all carried out by gunfire, and at the end of the play swastikas rained down onto the stage. The play received mixed reviews with many critics wondering why Seale had chosen to associate the Andronici with Nazism, arguing that it created a mixed metaphor.

Later in 1967, as a direct reaction to Seale's realistic production, Gerald Freedman directed a performance for Joseph Papp's Shakespeare Festival at the Delacorte Theater in Central Park, Manhattan, starring Jack Hollander as Titus, Olympia Dukakis as Tamora, Moses Gunn as Aaron and Erin Martin as Lavinia. Freedman had seen Seale's production and felt it failed because it worked by "bringing into play our sense of reality in terms of detail and literal time structure." He argued that when presented realistically, the play simply doesn't work, as it raises too many practical question, such as why does Lavinia not bleed to death, why does Marcus not take her to the hospital immediately, why does Tamora not notice that the pie tastes unusual, exactly how do both Martius and Quintus manage to fall into a hole? Freedman argued that "if one wants to create a fresh emotional response to the violence, blood and multiple mutilations of Titus Andronicus, one must shock the imagination and subconscious with visual images that recall the richness and depth of primitive rituals." As such, the costumes were purposely designed to represent no particular time or place but were instead based on those of the Byzantine Empire and Feudal Japan. Additionally, the violence was stylised; instead of swords and daggers, wands were used and no contact was ever made. The colour scheme was hallucinatory, changing mid-scene. Characters wore classic masks of comedy and tragedy. The slaughter in the final scene was accomplished symbolically by having each character wrapped in a red robe as they died. A narrator was also used (played by Charles Dance), who, prior to each act, would announce what was going to happen in the upcoming act, thus undercutting any sense of realism. The production received generally positive reviews, with Mildred Kuner arguing "Symbolism rather than gory realism was what made this production so stunning."

In 1972, Trevor Nunn directed an RSC production at the Royal Shakespeare Theatre, as part of a presentation of the four Roman plays, starring Colin Blakely as Titus, Margaret Tyzack as Tamora, Calvin Lockhart as Aaron and Janet Suzman as Lavinia. Colin Blakely and John Wood as a vicious and maniacal Saturninus received particularly positive reviews. This production took the realistic approach and did not shirk from the more specific aspects of the violence; for example, Lavinia has trouble walking after the rape, which, it is implied, was anal rape. Nunn believed the play asked profound questions about the sustainability of Elizabethan society, and as such, he linked the play to the contemporary period to ask the same questions of late twentieth-century England; he was "less concerned with the condition of ancient Rome than with the morality of contemporary life." In his program notes, Nunn famously wrote "Shakespeare's Elizabethan nightmare has become ours." He was especially interested in the theory that decadence had led to the collapse of Rome. At the end of 4.2, for example, there was an on-stage orgy, and throughout the play, supporting actors appeared in the backgrounds dancing, eating, drinking and behaving outrageously. Also in this vein, the play opened with a group of people paying homage to a waxwork of an obese emperor reclining on a couch and clutching a bunch of grapes.

The play was performed for the first time at the Stratford Shakespeare Festival in Ontario, Canada in 1978, when it was directed by Brian Bedford, starring William Hutt as Titus, Jennifer Phipps as Tamora, Alan Scarfe as Aaron and Domini Blithe as Lavinia. Bedford went with neither stylisation nor realism; instead the violence simply tended to happen off-stage, but everything else was realistically presented. The play received mixed reviews with some praising its restraint and others arguing that the suppression of the violence went too far. Many cited the final scene, where despite three onstage stabbings, not one drop of blood was visible, and the reveal of Lavinia, where she was totally bloodless despite her mutilation. This production cut Lucius' final speech and instead ended with Aaron alone on the stage as Sibyl predicts the fall of Rome in lines written by Bedford himself. As such, "for affirmation and healing under Lucius the production substituted a sceptical modern theme of evil triumphant and Rome's decadence."

A celebrated, and unedited production, (according to Jonathan Bate, not a single line from Q1 was cut) was directed by Deborah Warner in 1987 at The Swan and remounted at Barbican's Pit in 1988 for the RSC, starring Brian Cox as Titus, Estelle Kohler as Tamora, Peter Polycarpou as Aaron and Sonia Ritter as Lavinia. Met with almost universally positive reviews, Jonathan Bate regards it as the finest production of any Shakespearean play of the entire 1980s. Using a small cast, Warner had her actors address the audience from time to time throughout the play and often had actors leave the stage and wander out into the auditorium. Opting for a realist presentation, the play had a warning posted in the pit "This play contains scenes which some people may find disturbing," and numerous critics noted how, after the interval at many shows, empty seats had appeared in the audience. Warner's production was considered so successful, both critically and commercially, that the RSC did not stage the play again until 2003.

In 1988, Mark Rucker directed a realistic production at Shakespeare Santa Cruz, starring J. Kenneth Campbell as Titus, Molly Maycock as Tamora, Elizabeth Atkeson as Lavinia, and an especially well-received performance by Bruce A. Young as Aaron. Campbell presented Titus in a much more sympathetic light than usual; for example, he kills Mutius by accident, pushing him so that he falls against a tree, and his refusal to allow Mutius to be buried was performed as if in a dream state. Prior to the production, Rucker had Young work out and get in shape so that by the time of the performance, he weighed 240 lbs. Standing at six foot four, his Aaron was purposely designed to be the most physically imposing character on the stage. Additionally, he was often positioned as standing on hills and tables, with the rest of the cast below him. When he appears with the Goths, he is not their prisoner, but willingly enters their camp in pursuit of his baby, the implication being that without this one weakness, he would have been invincible.

In 1994, Julie Taymor directed the play at the Theater for the New City. The production featured a prologue and epilogue set in the modern era, foregrounded the character of Young Lucius, who acts as a kind of choric observer of events, and starred Robert Stattel as Titus, Melinda Mullins as Tamora, Harry Lennix as Aaron and Miriam Healy-Louie as Lavinia. Heavily inspired in her design by Joel-Peter Witkin, Taymor used stone columns to represent the people of Rome, who she saw as silent and incapable of expressing any individuality or subjectivity. Controversially, the play ended with the implication that Lucius had killed Aaron's baby, despite his vow not to.

In 1995, Gregory Doran directed a production at the Royal National Theatre, which also played at the Market Theatre in Johannesburg, South Africa, starring Antony Sher as Titus, Dorothy Ann Gould as Tamora, Sello Maake as Aaron and Jennifer Woodbine as Lavinia. Although Doran explicitly denied any political overtones, the play was set in a modern African context and made explicit parallels to South African politics. In his production notes, which Doran co-wrote with Sher, he stated, "Surely, to be relevant, theatre must have an umbilical connection to the lives of the people watching it." One particularly controversial decision was to have the play spoken in indigenous accents rather than Received Pronunciation, which allegedly resulted in many white South Africans refusing to see the play. Writing in Plays International in August 1995, Robert Lloyd Parry argued "the questions raised by Titus went far beyond the play itself [to] many of the tensions that exist in the new South Africa; the gulf of mistrust that still exists between blacks and whites […] Titus Andronicus has proved itself to be political theatre in the truest sense."

For the first time since 1987, the RSC staged the play in 2003, under the direction of Bill Alexander and starring David Bradley as Titus, Maureen Beattie as Tamora, Joe Dixon as Aron and Eve Myles as Lavinia. Convinced that Act 1 was by George Peele, Alexander felt he was not undermining the integrity of Shakespeare by drastically altering it; for example, Saturninus and Tamora are present throughout, they never leave the stage; there is no division between the upper and lower levels; all mention of Mutius is absent; and over 100 lines were removed.

In 2006, the play was staged at Shakespeare's Globe, directed by Lucy Bailey and starring Douglas Hodge as Titus, Geraldine Alexander as Tamora, Shaun Parkes as Aaron and Laura Rees as Lavinia. Bailey focused on a realistic presentation throughout the production; for example, after her mutilation, Lavinia is covered from head to toe in blood, with her stumps crudely bandaged, and raw flesh visible beneath. The production was also controversial insofar as the Globe had a roof installed for the first time in its history purposely for the play. The decision was taken by designer William Dudley, who took as his inspiration a feature of the Colosseum known as a valarium – a cooling system which consisted of a canvas-covered, net-like structure made of ropes, with a hole in the centre. Dudley made it as a PVC awning which was intended to darken the auditorium."

In 2007, Gale Edwards directed a production for the Shakespeare Theatre Company at the Harman Center for the Arts, starring Sam Tsoutsouvas as Titus, Valerie Leonard as Tamora, Colleen Delany as Lavinia and Peter Macon as

Aaron. Set in an unspecific modern milieu, props were kept to a minimum, with lighting and general staging kept simple, as Edwards wanted the audience to concentrate on the story, not the staging. The production received generally very favourable reviews.

In 2011, Michael Sexton directed a modern military dress production at The Public Theater on a minimalistic set made of plywood boards. The production had a low budget and much of it was spent on huge volumes of blood that literally drenched the actors in the final scene, as Sexton said he was determined to outdo his contemporaries in terms of the amount of on-stage blood in the play. The production starred Jay O. Sanders (who was nominated for a Lucille Lortel) as Titus, Stephanie Roth Haberle as Tamora, Ron Cephas Jones as Aaron and Jennifer Ikeda as Lavinia.

In 2013, Michael Fentiman directed the play for the Royal Shakespeare Company, with Stephen Boxer as Titus, Katy Stephens as Tamora, Kevin Harvey as Aaron and Rose Reynolds as Lavinia. Emphasising the gore and violence, the production carried a trailer with warnings of "graphic imagery and scenes of butchery." It plays in The Swan until October 2013.

Outside Britain and America, other significant productions include Qiping Xu's 1986 production in China, which drew political parallels to Mao Zedong's Cultural Revolution and the Red Guards; Peter Stein's 1989 production in Italy which evoked images of twentieth century Fascism; Daniel Mesguich's 1989 production in Paris, which set the entire play in a crumbling library, acting as a symbol for Roman civilisation; Nenni Delmestre's 1992 production in Zagreb which acted as a metaphor for the struggles of the Croatian people; and Silviu Purcărete's 1992 Romanian production, which explicitly avoided using the play as a metaphor for the fall of Nicolae Ceaușescu (this production is one of the most successful plays ever staged in Romania, and it was revived every year up to 1997).

FILM

In 1969, Robert Hartford-Davis planned to make a feature film starring Christopher Lee as Titus and Lesley-Anne Down as Lavinia, but the project never materialised.

The 1973 horror comedy film Theatre of Blood, directed by Douglas Hickox featured a very loose adaptation of the play. Vincent Price stars in the film as Edward Lionheart, regarded as the finest Shakespearean actor of all time. When he fails to be awarded the prestigious Critic's Circle Award for Best Actor, he sets out exacting bloody revenge on the critics who gave him poor reviews, with each act inspired by a death in a Shakespeare play. One such act of revenge involves the critic Meredith Merridew (played by Robert Morley). Lionheart abducts Merridew's prized poodles, and bakes them in a pie, which he then feeds to Merridew, before revealing all and force-feeding the critic until he chokes to death.

A 1997 straight-to-video adaptation, which cuts back on the violence, titled Titus Andronicus: The Movie, was directed by Lorn Richey and starred Ross Dippel as Titus, Aldrich Allen as Aaron) and Maureen Moran as Lavinia. Another straight-to-video- adaptation was made in 1998, directed by Christopher Dunne, and starring Robert Reese as Titus, Candy K. Sweet as Tamora, Lexton Raleigh as Aaron, Tom Dennis as Demitrius, with Levi David Tinker as Chiron and Amanda Gezik as Lavinia. This version enhanced the violence and increased the gore. For example, in the opening scene, Alarbus has his face skinned alive, and is then disembowelled and set on fire.

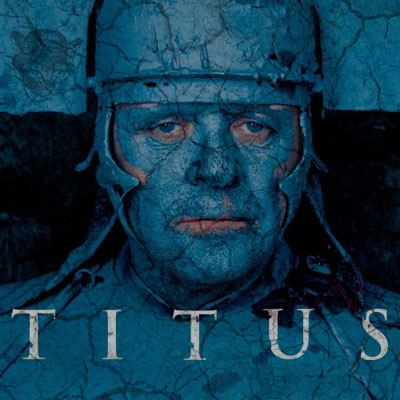

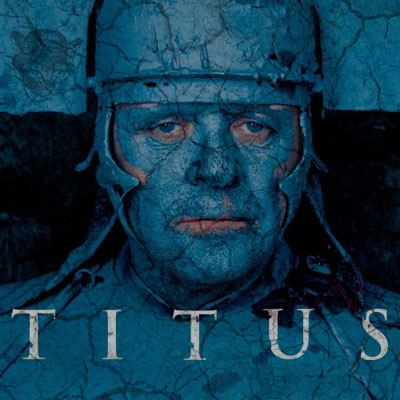

In 1999, Julie Taymor directed an adaptation entitled Titus, starring Anthony Hopkins as Titus, Jessica Lange as Tamora, Harry Lennix as Aaron (reprising his role from Taymor's 1994 theatrical production) and Laura Fraser as Lavinia. As with Taymor's stage production, the film begins with a young boy playing with toy soldiers and being whisked away to Ancient Rome, where he assumes the character of young Lucius. A major component of the film is the mixing of the old and modern; Chiron and Demetrius dress like modern rock stars, but the Andronici dress like Roman soldiers; some characters use chariots, some use cars and motorcycles; crossbows and swords are used alongside rifles and pistols; tanks are seen driven by soldiers in ancient Roman garb; bottled beer is seen alongside ancient bottles of wine; microphones are used to address characters in ancient clothing. According to Taymor, this anachronistic structure was created to emphasise the timelessness of the violence in the film, to suggest that violence is universal to all humanity, at all times: "Costume, paraphernalia, horses or chariots or cars; these represent the essence of a character, as opposed to placing it in a specific time. This is a film that takes place from the year 1 to the year 2000." At the end of the film, young Lucius takes the baby and walks out of Rome, which Taymor feels represents hope for the future. Originally, the film was to end as Taymor's 1994 production had, with the implication that Lucius is going to kill Aaron's baby, but during production of the film, actor Angus Macfadyen, who played Lucius, convinced Taymor that Lucius was an honourable man and wouldn't go back on his word. Lisa S. Starks reads the film as a revisionist horror movie and feels that Taymor is herself part of the process of twentieth century re-evaluation of the play: "In adapting a play that has traditionally evoked critical condemnation, Taymor calls into question that judgement, thereby opening up the possibility for new readings and considerations of the play within the Shakespeare canon."

William Shakespeare's Titus Andronicus, directed by Richard Griffin and starring Nigel Gore as Titus, Zoya Pierson as Tamora, Kevin Butler as Aaron and Molly Lloyd as Lavinia, was released direct to video in 2000. Shot on DV in and around Providence, Rhode Island with a budget of $12,000, the film is set in a modern business milieu. Saturninus is a corporate head who has inherited a company from his father, and the Goths feature as contemporary Goths.

SMOOTH

FACED GENTLEMEN - TITUS ANDRONICUS - SUMMER TOUR

All-Female Titus Andronicus from Smooth Faced Gentlemen - Ashlea Kaye & Leila

Sykes

The time is here – we can finally announce our plans for this Summer!

We’re a pretty new company, with big ambitions, so we’ve planned this year for two things: developing our own style, skills, and identity; and getting the work in front of as many people as possible!

So, it’s with great excitement we can confirm our 2013 Fringe Tour of Titus Andronicus:

We’ll be officially premiering the show at the wonderful Buxton Fringe (where last year we won the award for Best Production), performing again at Underground Venues‘ Arts Centre Studio.

We’re then high-tailing it up to the Edinburgh Fringe for a full three-week run at the beautiful Bedlam Theatre, world-renowned for being a hub of innovative new theatre companies on the Fringe. We’re honoured to be joining their programme, in the headline slot of 7:30pm.

From there, we’ll be taking the show further – more dates to be confirmed.

For those who aren’t familiar with it, Titus Andronicus is the first tragedy

Shakespeare wrote, and one of his most misunderstood plays. It tracks the feud between the families Titus, a respected warrior returning to Rome after a bloody victory, and his former prisoner – turned Empress – Tamora. It’s a vicious, visceral tale of revenge and responsibility, which, with its uncompromising brutality, was all but banned for best part of three centuries. There are

buckets of wonderful characters, only three of whom are women, and barely any of which survive!

Like our Romeo & Juliet, we’ll be cutting the play right down to a fast-paced action-packed comedy-fuelled 65 minutes of Shakespearean joy, presenting 27 characters with just eight actors. Ours will be a vibrant, energetic take, lovingly told with rigour and vigour and lots of coloured paint.

Can you tell we’re excited?

Smooth-Faced-Gentlemen-All-Female-Titus-Andronicus

We’re pleased to be welcoming Associate Director Yaz Al-Shaater back to direct the show, and once again, founder/Artistic Director Ashlea Kaye will fill the shoes of company manager and produce. Also on board to offer two very different approaches to Dramaturgy are Associate Director Tom Crawshaw and new collaborator Anna Beecher. We hope to work with Anna a lot more in the future, so why not get to know her by reading her recent contribution to our blog?

If you’re interested in joining our creative team, by the way, there’s still time to apply (see this post for job opportunities).

Peppered across this post are a sneak preview of our promo photos, artfully created by Haroun Al-Shaater from Brother Brother Studios, and featuring Leila Sykes and Ashlea Kaye.

All-Female Titus Andronicus - The Ladder

This year is a big one for us. When we conceived the company, all-female Shakespeare was a rarity in Britain, especially in the mainstream, and the idea of a company dedicated to the purpose was unheard of. Since then, the Donmar made waves with their all-female Julius Caesar, and the Globe have announced they’re touring an all-female Taming Of The Shrew from June.

We’ve got big plans for the future, and we hope you’ll join us at this exciting time as we set them in motion! Remember, to stay up to date, just join our mailing list, follow us on Twitter, or like our Facebook page.

See you at the Fringes!

This entry was posted in News and tagged buxton, edfringe, shakespeare, titus andronicus on March 21st, 2013 by The Gents.

See

them at the 2013 Buxton Fringe

TITUS

ANDROGYNUS

Last night I took part in a reading of Titus Andronicus with the all-female Shakespeare company, Smooth Faced Gentlemen. Having slightly turned away from this kind of theatre in the last few years in favour of devising and live art, it was strange and exciting to slip back into my Shakespeare shoes.

What struck me most (apart from the fact the play is a bit all over the place and there are clear reasons why it’s a lesser known work) was the inherent power of telling this brutal story with an all-female cast.

Smooth Faced Gentleman aren’t on a political mission, they just want to get their hands on Shakespeare’s great roles, which are almost all written for blokes. But, intentionally or otherwise, to me it felt deeply political. With all the roles taken by women, somehow the voices of the actual female characters Tamora and Lavinia took on a different quality. Naturally, I compared the play to Timberlake Wertenbaker’s The Love of The Nightingale, as both draw from Ovid’s Metamorphosis and centre on a woman being raped and violently silenced, with her tongue cut out to stop her naming her attackers.

Wereas Wertenbaker’s Philomele is the protagonist; Lavinia is more of a pivot for male-led action to revolve around. However, in the hands of Smooth Faced Gentlemen, with the male parts all read by female actors, Lavinia’s silence was somehow highlighted; here were all these female voices in the absence of hers. It made it harder for me to brush the rape aside as another gruesome plot point amongst many, my mind constantly returning to her silence, her silence filling the room. The most powerful scene for me last night, was in Act II, where Lavinia begs Tamora for help as Tamora’s sons try to rape her in the woods and Tamora refuses. We could see Tamora as like Aaron, her lover, who seems to be cruel without reason. And yet we can sympathise with Tamora, once a queen, then a prisoner, she becomes empress as a way of freeing herself, her only currency is her sexuality and she must use it cannily, even whilst grieving her murdered children. In light of this Tamora’s cruelty towards Lavinia seems more nuanced. We have to confront the reasons why women don’t always help each other, even in the modern world, women who trample on other women because there’s only so much space in the margins. And one thing an all-female cast does is remind you how marginalised women are in these stories, without ever pointing to it; we notice how few girls the girls are playing (three female characters out of about thirty!).

I think, despite it having one of Shakespeare’s weirdest plots (and in some ways because of it-the whole thing feels like a strange, dystopian, gruesome rollercoaster ride) Titus Andronicus is great play for a group of women to take on. There’s a reason why Ovid’s story from Metamorphosis continues to resonate, with the story of Philomele, raped, mutilated, silenced, popping up in poetry from Walter Raleigh to Elliot’s The Wasteland, prose like Margaret Atwood’s Nightingale and plays like Joanna Lauren’s The Three Birds and of course, The Love of The Nightingale. For me, as a feminist, the pairing of rape and silencing is what makes the story so powerful, evoking the idea of being able to vocalise desire as essential to taking ownership one’s sexuality so passionately argued in Yes Means Yes!: Visions of Female Sexual Power and a World Without Rape. Smooth Faced Gentleman may be political with a small p, liberating female actors from Shakespeare’s margins, but for me this simple act of telling these stories in women’s voices gives voice to women. It also encourages audiences to see characters as people rather than genders. With so few plays and even fewer films passing the Bechdel test, that feels radical in itself.

This article was originally posted on Anna Beecher‘s tumblog, and is reproduced here with her permission. See the original post on tumblr

This entry was posted in Thought and tagged feminism, gender, guest posts, shakespeare, titus andronicus on March 18th, 2013 by Anna Beecher.

|

Titus

Andronicus 1999 - Youtube

|

Titus

Julie Taymor - Youtube

|

LINKS:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Titus_Andronicus

http://smoothfacedgentlemen.com/news/

http://stuffofdreamsseries.blogspot.co.uk/2012/02/deconstructing-titus-andronicus.html

http://theaterbator.blogspot.co.uk/2011/08/dulaang-ups-titus-andronicus-sept-14.html

http://smoothfacedgentlemen.com/news/

Wikipedia

Bardfilm:

The Shakespeare and Film Microblog

Cambridge

History of Literature

Elizabethan

Authors

Francis

Bacon as Shake-speare

Henslowe's

Diary Online

International

Marlowe Shakespeare Society

Internet

Shakespeare Editions

Lost

Plays Database

Luminarium:

Anthology of English Literature

Marlowe

Society

Marlowe

Studies Online

On

the Tudor Trail

Patrons

and Performances

Performing

the Queen's Men

Peter

Farey's Marlowe Page

politicworm:Shakespeare

Authorship

Queen's

Men Editions

Royal

Shakespeare Company

Screenplay:

Theatre Plays on British Television

Shakespeare

in Quarto at the British Library

Shakespeare's

England

Shakespeare's

Globe

Shakespeare's

Words

Shakespeare-Oxford

Society

URL

of Derby

Who's

Who of Tudor Women

Rome

- Google Maps

Antony

and Cleopatra * Hamlet

* Macbeth * Othello * Romeo

and Juliet

A

Midsummer Night's Dream * As

You Like It * Much Ado About Nothing

The

Merchant of Venice * The Taming of the Shrew

* Titus Andronicus

Ashlea

* Camina

* Carly * Fran

* Henri * Kayleigh

* Leila * Mariam

History

becomes too real for comfort

for

an archaeological

expedition

|