|

The

genius of Shakespeare as a writer, was to begin with identifying a new

geographical location to be able to apply his successful formula for tragedy

and then concentrate on popularising the key historical elements.

ASSASSINATION

The Tragedy of Julius Caesar,

known simply as Julius Caesar, is obviously a tragedy by William Shakespeare, believed to have been written in

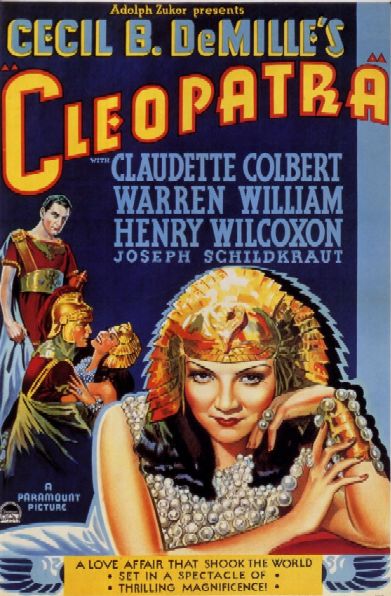

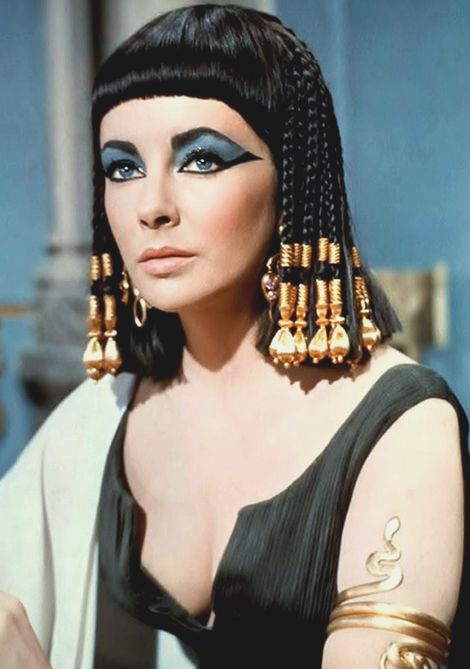

1599. It portrays the 44 BC conspiracy against the Roman dictator Julius Caesar, his assassination and the defeat of the conspirators at the Battle of Philippi. It is one of several Roman plays that Shakespeare wrote, based on true events from Roman history, which also include Coriolanus and Antony and Cleopatra.

Although the title of the play is Julius Caesar, Caesar is not the very best character in its action; he appears in only three scenes, and is killed at the beginning of the third act. Marcus Brutus speaks more than four times as many lines, and the central psychological drama is his struggle between the conflicting demands of honour, patriotism, and friendship.

SYNOPSIS

Marcus Brutus is Caesar's close friend and a Roman praetor. Brutus allows himself to be cajoled into joining a group of conspiring senators because of a growing suspicion—implanted by Caius Cassius—that Caesar intends to turn republican

Rome into a monarchy under his own rule.

The early scenes deal mainly with Brutus's arguments with Cassius and his struggle with his own conscience. The growing tide of public support soon turns Brutus against Caesar (this public support was actually faked; Cassius wrote letters to Brutus in different handwritings over the next month in order to get Brutus to join the conspiracy). A soothsayer warns Caesar to "beware the Ides of

March," which he ignores, culminating in his assassination at the Capitol by the conspirators that day, despite being warned by the soothsayer and Artemidrous, one of Caesar's supporters at the entrance of the Capitol.

Caesar's assassination is one of the most famous scenes of the play, occurring in Act 3 (the other is Mark Antony's oration "Friends, Romans, countrymen".) After ignoring the soothsayer as well as his wife's own premonitions, Caesar comes to the Senate. The conspirators create a superficial motive for the assassination by means of a petition brought by Metellus Cimber, pleading on behalf of his banished brother. As Caesar, predictably, rejects the petition, Casca grazes Caesar in the back of his neck, and the others follow in stabbing him; Brutus is last. At this point, Caesar utters the famous line "Et tu,

Brute?" ("And you, Brutus?", i.e. "You too, Brutus?"). Shakespeare has him add, "Then fall, Caesar," suggesting that Caesar did not want to survive such treachery, therefore becoming a hero.

The conspirators make clear that they committed this act for Rome, not for their own purposes and do not attempt to flee the scene. After Caesar's death, Brutus delivers an oration defending his actions, and for the moment, the crowd is on his side. However, Mark Antony, with a subtle and eloquent speech over Caesar's corpse—beginning with the much-quoted "Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears"—deftly turns public opinion against the assassins by manipulating the emotions of the common people, in contrast to the rational tone of Brutus's speech. Antony rouses the mob to drive the conspirators from Rome. Amid the violence, the innocent poet, Cinna, is confused with the conspirator Lucius Cinna and is murdered by the mob.

The beginning of Act Four is marked by the quarrel scene, where Brutus attacks Cassius for soiling the noble act of regicide by accepting bribes ("Did not great Julius bleed for justice' sake? / What villain touch'd his body, that did stab, / And not for justice?") The two are reconciled; they prepare for war with Mark Antony and Caesar's adopted son, Octavian (Shakespeare's spelling: Octavius). That night, Caesar's ghost appears to Brutus with a warning of defeat ("thou shalt see me at Philippi").

At the battle, Cassius and Brutus knowing they will probably both die, smile their last smiles to each other and hold hands. During the battle, Cassius commits suicide after hearing of the capture of his best friend, Titinius. After Titinius, who wasn't really captured, sees Cassius's corpse, he commits suicide. However, Brutus wins that stage of the battle - but his victory is not conclusive. With a heavy heart, Brutus battles again the next day. He loses and commits suicide.

The play ends with a tribute to Brutus by Antony, who proclaims that Brutus has remained "the noblest Roman of them all" because he was the only conspirator who acted for the good of Rome. There is then a small hint at the friction between Mark Antony and Octavius which will characterise another of Shakespeare's Roman plays, Antony and Cleopatra.

ANALYSIS

& CRITICISM

Historicism

Maria Wyke has written that the play reflects the general anxiety of Elizabethan England over succession of leadership. At the time of its creation and first performance, Queen Elizabeth, a strong ruler, was elderly and had refused to name a successor, leading to worries that a civil war similar to that of Rome might break out after her

death.

Protagonist debate

Critics of Shakespeare’s play Julius Caesar differ greatly on their views of Caesar and Brutus. Many have debated whether Caesar or Brutus is the protagonist of the play, because of the title character's death in 3.1. But Caesar compares himself to the Northern Star, and perhaps it would be foolish not to consider him as the axial character of the play, around whom the entire story turns. Intertwined in this debate is a smattering of philosophical and psychological ideologies on republicanism and monarchism. One author, Robert C. Reynolds, devotes attention to the names or epithets given to both Brutus and Caesar in his essay “Ironic Epithet in Julius Caesar”. This author points out that Casca praises Brutus at face value, but then inadvertently compares him to a disreputable joke of a man by calling him an alchemist, “Oh, he sits high in all the people’s hearts,/And that which would appear offence in us/ His countenance, like richest alchemy,/ Will change to virtue and to worthiness” (I.iii.158-60). Reynolds also talks about Caesar and his “Colossus” epithet, which he points out has its obvious connotations of power and manliness, but also lesser known connotations of an outward glorious front and inward

chaos. In that essay, the conclusion as to who is the hero or protagonist is ambiguous because of the conceit-like poetic quality of the epithets for Caesar and Brutus.

Myron Taylor, in his essay “Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar and the Irony of History”, compares the logic and philosophies of Caesar and Brutus. Caesar is deemed an intuitive philosopher who is always right when he goes with his gut, for instance when he says he fears Cassius as a threat to him before he is killed, his intuition is correct. Brutus is portrayed as a man similar to Caesar, but whose passions lead him to the wrong reasoning, which he realises in the end when he says in V.v.50–51, “Caesar, now be still:/ I kill’d not thee with half so good a

will”. This interpretation is flawed by the fact it relies on a very odd reading of "good a will" to mean "incorrect judgements" rather than the more intuitive "good intentions."

Joseph W. Houppert acknowledges that some critics have tried to cast Caesar as the protagonist, but that ultimately Brutus is the driving force in the play and is therefore the tragic hero. Brutus attempts to put the republic over his personal relationship with Caesar and kills him. Brutus makes the political mistakes that bring down the republic that his ancestors created. He acts on his passions, does not gather enough evidence to make reasonable decisions and is manipulated by Cassius and the other

conspirators.

Traditional readings of the play may maintain that Cassius and the other conspirators are motivated largely by envy and ambition, whereas Brutus is motivated by the demands of honour and patriotism. But one of the central strengths of the play is that it resists categorising its characters as either simple heroes or villains. The political journalist and classicist Garry Wills maintains that "This play is distinctive because it has no

villains".

It is a drama famous for the difficulty of deciding which role to emphasize. The characters rotate around each other like the plates of a Calder mobile. Touch one and it affects the position of all the others. Raise one, another sinks. But they keep coming back into a precarious

balance.

Wills' contemporary interpretation leans more toward recognition of the conscious, sub-conscious nature of human actions and interactions. And in this the role of Cassius becomes paramount.

The conspirators know Caesar. He has defeated opponents on the battlefield and conquered for Rome, half the known world. He has vanquished his political, governmental, military and bureaucratic, opponents in Italy and Rome. He has beaten them in fair and unfair fights; he has outmaneuvered them into hopelessness; he has cajoled them to declaim their positions and accept his mastery; he has appeased them, allied with them, and then absorbed them, leaving only Caesar standing alone, in the place an opponent was.

The “republican” faction in the Roman Senate knows that Caesar is “still on the march”, and this time his opponent is them, the Senate, as an institution. They know that “their” Senate, as an institution has, in opposition to Caesar, only two choices; surrender or oblivion. They should disappear like the fog or mist vanishes in plain sight with the rising of the sun.

The conspirators in general; and, Brutus in particular, each have, like a Wills’ Calder analogy, an unacknowledged, yet very, real binding relationship to one another. It is their both singular and collective growing hostility and fear of Caesar the political and personal man. Their fears are both self-sustaining, and mutually reinforcing, one upon the other.

Cassius like a modern psychoanalyst perceives in Brutus, his sub-conscious, inchoate fear, hostility, even loathing, of a man (Caesar) that he outwardly claims he both loves and admires. It is Cassius who perceives this colorless, odorless, “something in the air”; which, if he can tap into its organizing and animating power in and over Brutus, will motivate Brutus to enlist, to organize, to persuade, and to sustain to completion, the act of conspiracy and brutal murder; as an action of loyal, loving, patriotism. It is Shakespeare at his most dramatically sophisticated, psychological best.

Cassius does not lead himself, Brutus, or the rest of the conspiracy, as lambs to the slaughter. He knows what he is doing; and, unlike Iago in Othello, he does not occasionally turn to the audience and literally tell us what is going to happen as a result of his subtle psychological manipulation of people and/or events. But if the dialog is followed closely, Casssius’ recognition of what he has to do, and how he has to coordinate the interaction of pieces of his “Calder” mobiles, is perfectly clear.

But in the final analysis these men are drawn together not by external forces they do not perceive or understand, but by their motivations of greed, ambition, fear, loathing, mistrust; and, the realities of their all too human ignorance, misjudgment, bad judgment, bad luck, and their refusal to “see” the truth of the individual and collective motivations that underlay their actions. As usual that human failing always leads ordinary men, real (as opposed to fictional ideal) men into the tragedy that is their lives.

Performance history

The play was likely one of Shakespeare's first to be performed at the Globe

Theatre. Thomas Platter the Younger, a Swiss traveller, saw a tragedy about Julius Caesar at a Bankside theatre on 21 September 1599 and this was most likely Shakespeare's play, as there is no obvious alternative candidate. (While the story of Julius Caesar was dramatised repeatedly in the Elizabethan/Jacobean period, none of the other plays known are as good a match with Platter's description as Shakespeare's

play.)

After the theatres re-opened at the start of the Restoration era, the play was revived by Thomas Killigrew's King's Company in 1672. Charles Hart initially played Brutus, as did Thomas Betterton in later productions. Julius Caesar was one of the very few Shakespearean plays that was not adapted during the Restoration period or the eighteenth

century.

|

Julius

Caesar - Youtube

|

RSC - Youtube

|

|

Rome

- Youtube

|

C

farewell - Youtube

|

LINKS:

Julius

Caesar text edited by John Cox, facsimiles of the 1623 Folio text

Internet

Shakespeare Editions

Julius

Caesar Navigator Includes Shakespeare's text with notes, line numbers

No

Fear Shakespeare Includes the play line by line with interpretation.

All

Julius Caesar Provides a summary of the play

Julius

Caesar – searchable, indexed e-text

Julius

Caesar – from Project Gutenberg

Julius

Caesar – by The Tech

Julius

Caesar – Searchable and scene-indexed version.

Julius

Caesar in modern English

Lesson

plans for Julius Caesar at Web English Teacher

Quicksilver

Radio Theater adaptation of "Julius Caesar at PRX.org (Public

Radio Exchange)

Julius

Caesar study guide

Wikipedia

Egypt

- Google Maps

Antony

and Cleopatra * Hamlet

* Macbeth * Othello * Romeo

and Juliet

A

Midsummer Night's Dream * As

You Like It * Much Ado About Nothing

The

Merchant of Venice * The Taming of the Shrew

Ashlea

* Camina

* Carly * Fran

* Henri * Kayleigh

* Leila * Mariam

History

becomes too real for comfort

for

an archaeological

expedition

|